In Defense of Friction

Brian Wilson, pantry pasta, and the possibility of a smartphone-free existence.

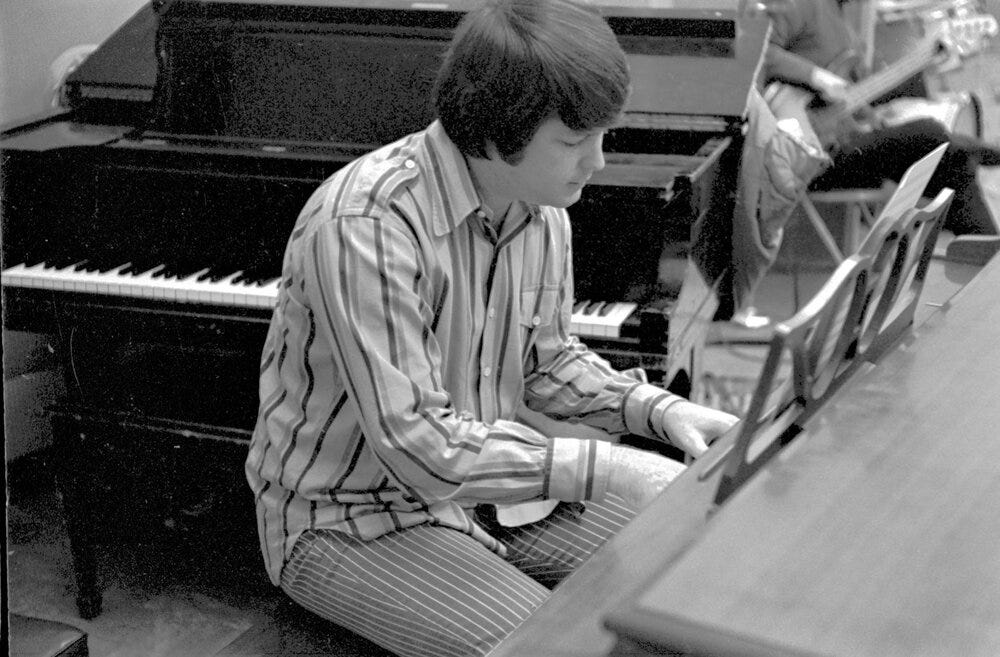

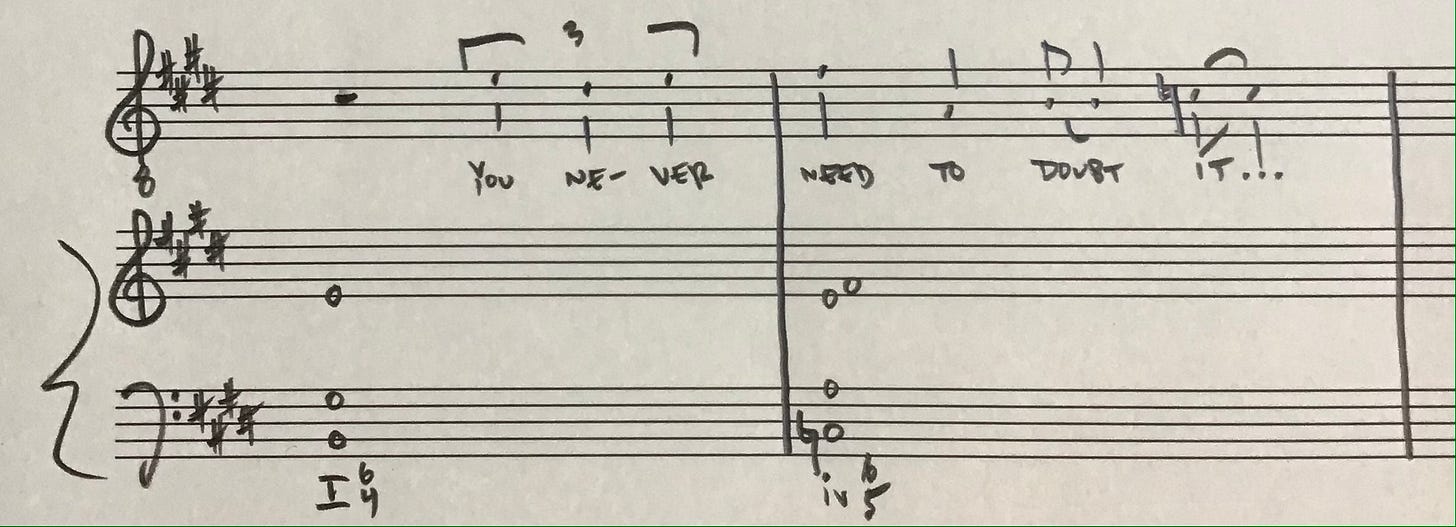

I want to make the case for you to get rid of your smartphone. But in order to do that, I need, first, to talk about Brian Wilson. And more specifically, about one of his most beloved songs. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: the bustling pulse of a harpsichord, stately but jocular, outlines a simple, baroque progression in E major— IV - I/6 - ii - I/6. A french horn enters—the high school valedictorian puffing out his chest while giving a commencement speech—goofy, poised, and awkward. At the midpoint of the phrase, an electric bass appears, along with—are those sleigh bells? And then, suddenly, we’re thrown into a distant tonal center…

What’s this? The intro suggested E major, but now, with the arrival of the verse, the harmonic field shifts. Sure, the A in the bass is familiar, but the notes above suggest something else—D major—a distant relative of the home key. You are wandering a foreign city in a light rain after dark. You peer down an alley, see café lights and walk faster. After that plaintive triplet that launches the tune (“I may not”), the harmony darkens: as the bass climbs upward on the word “always,” we get B minor dusted with that acidic C# appoggiatura in the melody. Inching closer, your stomach drops when you discover that this is not a watering hole but an undertaker’s office lit for the night shift. You’ve seen something you wish you hadn’t, and hurry away in the opposite direction. And now, something of a resolution, into F# minor:

From that quasi-cadence, the bass climbs back up to A. You had made plans to meet a new acquaintance at a bar, a few kilometers from the hotel; you have a map and an address, you know you’re close, and yet… And yet, the tones above have a mind of their own, outlining a B major triad, which, in combination with the A, forms a dominant seventh chord in third inversion, a Brian Wilson Special™. We might hear this as a kind of tone painting: the harmony brightening just before the word “stars” is sung. Note, also, that the melody has inverted itself; what had been a falling shape now ascends heavenward : more tone painting. You huddle under the doorway of a patrician-looking townhouse, using the light that leaks through the panes of glass to orient yourself on the map. You’ve righted yourself and walk closer to the canals, lit by the moon.

Now, this chord, that inverted dominant seventh, has a magnetic force; we long to hear the bass slip from A to G#—scale degree 4 to scale degree 3—a classic baroque move. But Brian Wilson is a sneaky guy. He gives us resolution to E major in the quality of the chord that follows, but the bass goes up instead of down, so we are both home and away. You took a wrong turn. You’re lost again. But it’s alright.

From that place of near resolution, we now get a chromatic neighbor, C natural, in the bass, a pungent turn, an A minor chord with the added funk of a sixth (F#), suggesting that a plagal cadence may be ahead…

And indeed, we do get E major, but again, it’s accompanied by that ambiguous B in the bass. You stop for a moment to breathe the late winter air, feel the raindrops on your ears and forearms and the back of your neck. You are just… there. And now, the money shot: the half-diminished chord on “sure” — the height of harmonic instability set against a word of certainty. But there is a sense of direction to the harmony: the A# in the bass has an ineluctable need to move on; if this chord didn’t break your heart, then the next one will…

And sure enough, there’s the A in the bass once more. This time, after all of their various jaunts, the tones above have decided to cooperate, and we get crystalline A major, the subdominant, where the intro began. We fall, happily, into that serene hook… You see your new friend through the window of the bar, all amber light, laughter, the clinking of glass.

Only now do we understand that that introduction foreshadowed the chorus, the movement of IV - I/6 - ii - I/6 having given us the foundation without the facade. The miracle of the song, for me, is how the various harmonic gambits, though they seem to meander, combine to form a single, precise excursion headed toward resolution. I love, too, how this sense of quest, of a series of doors being cracked upon, a room peered into, then shut again, mirrors the spiritual mystery in the lyric. The power of the chorus derives not only from its simplicity, but from the fact that it emerges out of such a harmonic thicket. It is a journey through dissonance — through friction — that makes for such a satisfying arrival back into pure E major.

On a rainy evening in February of 2020, I wandered the streets of Amsterdam, trying to find the bar where I’d agreed to meet up with a writer who’d attend my gig at a matchbook-sized club the night before. I was three months into my year-long hiatus from the internet, and this solo tour of Europe — thirteen cities in three weeks — was the thing I’d been most apprehensive about. Sure, I’d grown up in the pre-smartphone era, knew how to read a map, and so on. But still! What if I missed a train transfer in France? How was I going to find the best spaetzle in Hamburg? How would I convey to my friend Pekka that I was waiting for him at baggage claim in Helsinki, arms sore from weeks of lugging boxes of LPs from hotel to merch table to taxi and back again?

As it happened, everything went fine. (Though I ate no spaetzle in Hamburg, I did find my friend at the bar in Amsterdam, and the tour went off largely without a hitch, small audiences notwithstanding.) And, as I often found throughout my year offline, the friction I’d welcomed into my life was clarifying, even edifying. The dissonances I had to wade through made me appreciate the resolution, arrival, and cadence, all the more.

Just as we need certain things to suck in order for others to register as cool (Beavis and Butthead, 1994, MTV), so too must we experience resistance or difficulty (read: friction) in order to understand the nature and depth of our own desires.

Only a few weeks into my hiatus, I realized how much my sense of necessity had been shaped by convenience, by lack of friction. If nothing else, this saved me a ton of money. Without an internet connection, impulse buys were out of the question. I made do without contact-less delivery of pastured pork dumplings, Alsatian white wines, and smart toothbrushes, not to mention the 3,285,317 bits of trivia that I couldn’t Google. The widgets or information I still longed for? Those, I managed to get, and yes, it often took more time and effort. And I was all the more grateful for them when they arrived.

The skeptic might respond: “most people’s lives are already chockablock with friction and tedium. These are often functions of poverty. The whole premise of your argument is distasteful. And besides, the pace of my job and demands of family life will not accommodate additional friction.”

All of this seems eminently reasonable. But permit me to push back. First, I’d say that I have a fairly specific audience in mind: people of economic means whose online activities have a disproportionate impact on labor and the environment. (More on that later; N.B. I wrote in an earlier post about the ripple effect attendant to social media posts by famous people.) Second, I would add: to the extent that your life may be stuck in hyperdrive, perhaps it’s because you’ve been shackled to an economy that makes an ouroboros of efficiency. How did we get here?

Here is Lewis Mumford, writing in 1934:

The clock, not the steam-engine, is the key-machine of the modern industrial age…even today no other machine is so ubiquitous…

Still true! Following Mumford, we can trace a path from the medieval monk praying by the hours of the clock to the office worker staring into the void of a screen. When the clock was adopted by merchants in the countinghouse in the thirteenth century, profit supplanted piety; money replaced God. Over time, the length of the workday became fixed, so that technological innovation—the steam engine, the telegraph, the fiberoptic cable, the AI that translates your behavior into futures markets in which advertisers bid for your attention—ceased to be labor-saving, and instead facilitated more work in the same amount of time. By this logic, the smartphone’s fundamental utility, often elaborately concealed under the guise of entertainment or social connection, is the elimination of friction from capitalist exchange.

Because these technologies are often wielded by large corporations whose interests lies in profit— often in diametric opposition to the quality of its employees’ lives—the laborer cranks out more widgets, while her leisure time seldom increases. If anything, it has decreased. Indeed, in my experience, everyone seems busier now than they were fifteen years ago, when the iPhone was introduced. Scheduling drinks with an old friend now requires doodle polls, voluminous email volleys, an army of executive assistants. Then, you suck down your Negronis in 47 minutes, before rushing off to your respective work dinners or next round of drinks. And it gets worse.

Frictionless exchange almost always involves an unseen toll. One of the most insidious features of our digital regime is the way in which it mystifies the role of labor in daily economic life. When we order a pack of medium-bristle, glow-in-the-dark, MCU-themed toothbrushes from the dude whose e-commerce empire funds an elaborate Captain Picard cosplay, we don’t see the employee on the fulfillment center floor, working through a fever and a herniated disc or pissing into a bottle for fear of termination should they fall behind on their quotas. Nor do we picture the energy required—and attendant carbon emissions belched into the atmosphere—to manufacture all the widgets we buy. And these purchases, I might add, are often made not out of any particular need, but because this stage of capitalism has delivered us within nanometers of a paradigm in which we think of a desire and see it instantly consummated.

Few devices have done more to obscure the efforts of human labor than the smartphone. Fewer still have vacuumed out of our lives as much human interaction as has been lost to our oblong, digital assistants.

Put away your phone, and observe how friction conjures the unexpected. Friction, as you wake in a dark hotel room and find yourself ecstatically untethered, making your way bleary-eyed through the lobby and onto the street, where you are alert to the noise of traffic, the collective hum of voices, the angles of tall buildings with facades of glass glazed sea-green, where you get lost amidst a throng of strange bodies and the rhythms they make in a city that isn’t yours, where you duck into a bookstore and find yourself in conversation with the bookseller about your shared love of Joy Williams and W.G. Sebald and later find a mis-shelved volume even more apposite to your line of inquiry than the book you thought you were seeking.

Friction makes us resourceful. It’s looking at a bare pantry, putting a pot of water onto boil, taking that solitary can of chickpeas from the shelf, cooking them down with a little garlic and chili flake and olive oil, tossing the sauce with the half-box of pasta hidden in the recesses of the cupboard, along with a bit of the cooking water, a deeply satisfying meal, and one you probably wouldn’t have made if you’d had 4,162 restaurant delivery options at your fingertips.

Friction can be social: a spark, a look. Friction, as the woman on the sidewalk approaches the house party on a June night; you sitting on a two-seater swing on the porch and wondering if she’ll join you. Friction, in the encounters we have with strangers who become friends, friends who become lovers; then the single lover with whom, having navigated a constellation of difference, you open yourself to a new dimension of joy and difficulty: the children whom you desperately love and who daily make you think you will lose your damn mind. And so on.

We spend a great deal of time lamenting the role that specific platforms and pieces of software play in sowing discord in society—I certainly have—but it’s worth widening the lens in order to examine the hardware that houses nearly all of it. For, in my view, it is the presence of powerful computers in our pockets, much more than it is any one platform or app, that drives the values of our society. We are everywhere connected, and yet we are unable to connect.

As our phones become ever more ubiquitous in the daily business of our lives—helping us to buy plane tickets, post selfies, order tacos and town cars, or to dash off emails and text messages to friends and colleagues—the ease with which we complete each task reinforces the fiction that efficiency and convenience have intrinsic value. That fiction, in turn, gives weight to the belief that the smartphone is an indispensable appendage for each of us. Notably, technology companies depend on our embrace of this myth, for a loss of faith in it would signal an existential threat to the devices’ manufacturers, and to all the software companies whose products depend on our fanatical devotion to convenience at all costs.

And so it is that we are, minute by minute, fed pabulum laced with little hits of instant gratification. It’s a world in which we get the hook of “God Only Knows” on a recursive loop, shorn of context. (This is not a metaphor. Go to a streaming service or digital music store; they’ll no doubt have the audio sample cued up to the chorus.) Me, I long for the searching harmonic journey, the spiritual quest, the slippery chromaticism that prepares the sonic parting of clouds, that makes that delayed resolution feel like nothing less than catharsis.

I'm quickly becoming persuaded your essay writing is every bit as enjoyable as your songwriting and musical composition. Your points are always thoughtfully argued, while your prose style sparkles with nerdy brio. For what it's worth, I spent the next two hours immersed in God Only Knows - on the internet, I might add, which made it fairly frictionless to discover. Thanks!

I thoroughly enjoy that you're using the internet to share your non-musical thoughts with us as well as the musical ones. Long may that continue. I'm in the midst of reading Shoshana Zuboff's book and accordingly have also become more disturbed about our gadgets spying on us, but I also think that--just generally in society, not in this essay necessarily, or in Zuboff's book--there's a tendency towards helplessness in the face of our digital overlords and an all-or-nothing approach to combating "the algorithm" that I find problematic.

Before I play devil's advocate any further, I do honestly applaud your fortitude in giving up the internet for an entire year, but those of us who are weaker can (and should and have the ability to) mediate our use of it. We ARE still in charge in many ways--we can turn off notifications and our location, we can curate our social media feeds and listen deliberately rather than being fed algorithmic content, we can use our phones to find a recipe rather than to order from one of those 4162 restaurants. Ani DiFranco said "every tool is a weapon if you hold it right," but I would invert that and declare that every weapon can also be a tool. And we can still attempt to hold this one correctly, even if parts of it are owned by billionaires.

And now I'm going to go use the internet to listen to your new album (which I adore) a few times. Because I can do that.