Kill Your Darlings

On the joy of editing.

Editing is like flossing your teeth. It’s an activity that everyone claims to do, knows to be salutary, and yet! While many young artists swear they edit their work fastidiously, my experience as an educator suggests that for many, editing—to go full metaphor—consists of taking a container of floss out of the medicine cabinet, looking gravely at the stuff for fifteen seconds, then shoving it back onto the shelf without so much as a thread having trespassed the fleshy perimeter of one’s lips, let alone gum line.

There is, among artists and audiences alike, an unhelpful myth that would have us believe that art is birthed in its mature state. This, I think, is a variation of the “lone genius” view of art-making, in which the composer, painter, or playwright sits in a chamber—ideally drafty and mouldering (underfed black cat, optional)—summoning radically original ideas from thin air. In fact, nearly all great art is, at least to some degree, the product of intertextuality: of one artist learning from, commenting on, stealing from, iterating and improving upon the work of her colleagues.

This process does not happen all at once, just as a work of art doesn’t migrate effortlessly and instantaneously from the brain to the page. When we discuss musical talent, we too often concern ourselves with innate physical, aural, or imaginative ability, at the expense of the unsung skill that allows those other qualities to flourish: namely, work ethic. One of the chief pleasures of my professional life has been getting to witness, up close, the discipline (in both sense of the word) of friends and colleagues, and to have been prodded through their example into a more rigorous creative routine, myself.

It’s a bit navel-gazey to buttress an essay on editing with examples from one’s own work, but let’s face it, my own drafts are the ones to which I have easiest access. Plus, I think there’s value for younger artists in peering behind the veil and observing how much tinkering goes into writing, in this instance, three verses and a chorus. To be sure, everyone’s process is different; I can only offer a glimpse into mine.

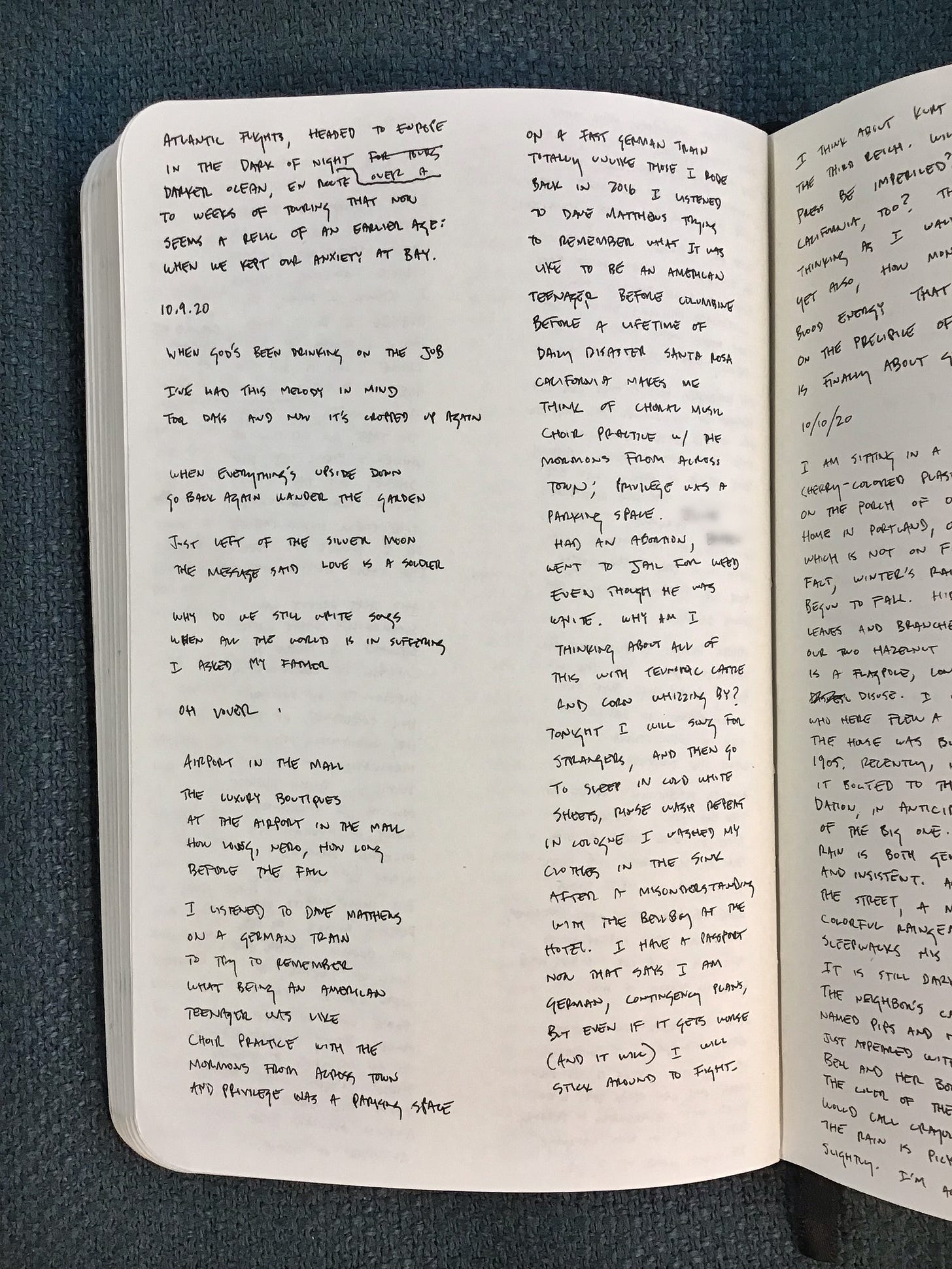

In October 2020, the final month of my year off the internet, I embarked on a daily writing practice. I would start each morning with a longhand free-write, continuing either until I felt I “had something,” or until my hand began to cramp.

On October 9th, I picked up where I’d left off the day before. The final verse of the song I’d written on the 8th—”Die Traumdeutung”—recalls pre-pandemic (or pre-apocalyptic) tours of Europe. What followed the next morning was, you might say, nested nostalgia: a recollection of traveling by train in Germany in February of 2020, and experiencing, during the course of that journey, a wave of memory originating in my adolescence in Northern California in the late ‘90s.

I notice a few things in looking back at this free-write.

1. It’s an undigested mess.

2. It is riddled with clichés and treacly pabulum.

3. There are two clues to the song that it would become, both underlined in red:

“I’ve had this melody in mind / For days and now it’s cropped up again” is what songwriters call a “dummy lyric.” Often, it’s just the first set of words that come to you bearing the right number of syllables and correct stresses for an extant tune. While a number of my songwriting colleagues always begin with music and then write lyrics, it is unusual for me to have a musical idea in my ear when I start working on a song. But in this case, the sketch indicates that I had a melody… in mind.

In the second column, buried amidst some stream-of-consciousness rambling, is a phrase that would become, in a slightly altered form, the title of the song, as well as its opening lyric.

On this particular day, I had written just about a page when I decided it was time to head out to my studio to type up what I’d written, as I did each morning that month. I would then print it, mark it up, type up the revisions, and print again, continuing this process until the shape of a lyric—whether through rhyme, scansion, structure, story, or some combination of the above—began to emerge. Here’s the third draft:

I don’t need to point out how cringe-inducing some of these lines are, though “Before I leave this fever dream / I offer one last parting thought” is spectacularly bad, hearkening back to some nightmarish vision of seventh-grade poetry class. The point, I think, is that in order to write something decent, you have to be comfortable putting garbage onto the page, to will yourself into the belief that nothing you write is permanent (it’s not!), and to embrace the notion that the product is, truly, in the process.

Admittedly, there are, even for me (a chronic tinkerer), those rare instances in which a song appears out of the ether, but that’s the exception and not the rule. In this draft, for example, the outline of the song has begun to come into focus, but there’s still a great deal of tweaking and distilling to be done. To revise is to be patient. To revise is to be generous toward oneself, to give oneself permission to be unfiltered, crude, sentimental, mawkish, experimental, dumb, speculative.

At the risk of beating a dead horse, I want to connect this meditation on revision to my idée fixe—our collective obsession with convenience and efficiency—and to underline again how much our culture (and its underlying economy) rewards, and is governed by, the pursuit of instant gratification (c.f. Twitter). In such an environment, one that encourages the creation of content for content’s sake, it’s unsurprising that young artists would want to just keep churning stuff out, rather than refining, sharpening, shaping a single work.

Let it be said, there is value in making things in an undigested way in order to strengthen our generative muscles, just as there’s a danger in becoming so obsessed with a single art object that it becomes tortured or overworked. Still, I hope that in opening up the hood of my songwriting clown car, one or two of you might be inspired to fall in love with the act of editing, to revel in erasure, to find joy in killing your darlings.

And in the meantime, here’s the finished song.

As a reminder, I’m heading back out on tour next week. Complete dates are here, with more to be announced in the coming months.

As a writing teacher I obviously applaud this, but as a writer who's been editing and rewriting a book for literal years (a book that as of this morning took a leap toward publication), I especially cheer the part about patience.

I also tell people that writing song lyrics is far and away the hardest kind of writing I've done, especially if you have a meter that repeats across multiple verses of the same music. It's demanding in a way that even poetry isn't (because poetry allows for greater metrical flexibility). Your lyrics tend to achieve a kind of effortless flow, and I'm glad to see the work that goes into getting there.

I’d appreciate your mutual subscribing to my Substack “Notes from a Old Drummer”