slurring our words

on palestinian liberation, ideological purity, the word "zionist," and more...

It’s been eighteen months since I’ve written about the catastrophe in Gaza, which continues with no sign of relent. The degree of human suffering is all but unimaginable. Benjamin Netanyahu, emboldened by his messianic stooges, Smotrich and Ben-Gvir, has now made explicit what many suspected all along: that his government intends to use Hamas’ massacre of more than one thousand Israelis on October 7 as a pretext for the ethnic cleansing of the entire Gaza Strip, while the expansion of illegal settlements in the occupied West Bank accelerates. Americans’ support for Israel has cratered, and yet our government continues to furnish Bibi with weapons and cash. And then there’s Iran.

Here at home, the Trump Administration has weaponized antisemitism to further its nativist and authoritarian agenda. It has made political prisoners of Palestinian activists, and threatened to withhold visas from anyone engaged in “antisemitic behavior” (read: pro-Palestinian activism or speech), even as the President chums it up with white nationalists. All of this has made good-faith discussions of antisemitism— which is thriving on both sides of the political spectrum—all but impossible.

At the same time, political violence, spurred by increasing fury at Israel, is on the rise. While mainstream media and political leadership have reflexively categorized these incidents as antisemitic, a more nuanced discourse is playing out in the little magazines. Whether or not one believes the attacks in Washington, D.C., and Boulder were motivated by Jew hatred (as opposed to anger at Israel), most observers recognize that these horrific acts do not advance the cause of Palestinian freedom. As Daniel May wrote in a probing essay for Jewish Currents:

the idea that these marchers in Boulder might be an apt target for violence… reflects a warped perspective in which distinctions between identity, complicity, responsibility, and power have dissolved. Even if the boundaries between these categories aren’t always clear, delineating them remains important. Their collapse isn’t, unfortunately, unique to any one assault; it is all too familiar in a political culture in which questions of power are often reduced to matters of identity. We’re not immune to this on the left, where degrees of responsibility are frequently flattened into a catchall “Zionist” identification.

Indeed, the transformation of the word “Zionist” into a slur is at a troubling apex, instantiated by a recent episode of Joshua Citarella’s podcast, Doomscroll, during which he invited Hasan Piker to “play a game” in which the goal was to identify whether a quote had been uttered by a Zionist or a Nazi. What seems lost on many young people—or anyone new to the history of Zionism—is just how contested the project of Zionism was within Israel until the last decade or two, and how contested it remains within the United States. The right-wing political Zionism now dominant in Israel, and among its most ardent adherents abroad—one rooted in hatred, racism, and the desire not merely to occupy the land of, but to eradicate, the Palestinian people—represents but one among many expressions of Zionism that competed for primacy in the first century of the movement’s existence. In fact, certain strains of cultural Zionism rejected the centrality of the nation-state in their self-conception, and were focused instead on the construction of a spiritual (rather than political) homeland for the eternally rootless Jew, a space that would not only acknowledge, but exhibit deference toward, those already living on the land. Needless to say, that vision of Zionism, along with a once robust Israeli left, has been all but vanquished. It is a heartbreaking irony that the Israeli-American left-wing activist Hayim Katsman, murdered by Hamas on October 7th, argued in a posthumously published essay for the renaissance of precisely this type of Zionism, rooted in pluralism and equality.

Holding the left to account for its distortion of the word “Zionist” is not mere tone-policing: language, it turns out, has consequences for the growth and resilience of political movements. Hundreds of thousands of American Jews who profess a connection to the state of Israel—and thus identify with some aspect of Zionism—also oppose the Netanyahu regime, the slaughter of innocent civilians in Gaza, and the illegal occupation of the West Bank. They ought to be welcomed into the coalition of those fighting for Palestinian dignity and self-determination. But in the American left’s hunger for ideological purity, many have adopted a litmus test that places political outcomes—the insistence that Israel become a secular, binational state—ahead of human rights. In doing so, they have shunned and often shamed liberal Zionists who would prefer a two-state solution, even as they share, with leftists, a deeply held belief in the Palestinian right to dignity and freedom. As I wrote a few months ago, coalitions require discomfort. Surely, though, we needn’t expect our potential allies to accept being called Nazis.

It’s particularly troubling to see the word “Zionist” used as a pejorative by my fellow left-wing diaspora Jews. While hardcore supporters of the Israeli regime accuse these leftists of being kapos or self-hating Jews, I think the truth is more complicated: that in today’s culture of purity politics, there are “good Jews” and “bad Jews,” and, in an effort to prove their bonafides, some left-wing diaspora Jews have come to wield the term “Zionist” as a shield, as evidence that they have the correct opinions, and might thus preserve their good-standing within an ideological clique. But we of all people should know that dehumanizing a vast, diverse group in order to increase our own social standing is corrosive, not only to them, but to ourselves. And it’s also evidence of a failure of imagination.

For many of us, myself included, it is a dumb accident of history to have been born in, say, Los Angeles, rather than Tel Aviv, or to have been raised in a family with virtually no ties to Israel, as opposed to one teeming with cousins, aunts, and uncles on the other side of the ocean. My ancestors fled Germany and Eastern Europe for the U.S. when they could just as easily have ended up in Palestine. In a counter-life, I might have lost friends or family in one of the hundreds of suicide bombings carried out by Palestinians between 1994 and 2005. Grief-wracked, perhaps I would have become saturated by hate and suspicion, and come to live, as most Israelis do today, without much sense of, or concern for, what happens in the West Bank or in Gaza, shielded from those grim realities by physical walls and censored media.

But this isn’t what happened. I was born in a small bungalow in Venice Beach, California, to secular Jews who were indifferent to my refusal to go to Hebrew school, where, had I attended, I would have been inculcated into the trauma-soaked narratives that fuel American Jewish attachment to the Holy Land. I have never been to Israel. I know virtually no one who lives there. In short, my left-wing politics regarding Israel/Palestine have cost me nothing. They exist largely in an abstract realm, devoid of tension or material consequences. The same cannot be said for many American Jews, and even less so for Palestinian or Israeli peace activists who continue to offer and receive grace, to and from one other, even amidst ongoing, devastating loss, the brunt of which is, of course, experienced by Palestinians.

What I admire in activists like Rula Daood and Alon Green, Palestinian and Israeli leaders of the group Standing Together, is that they are guided by the lived knowledge that their fates are intertwined. This is the essence of any kind of movement building, whether it’s a union drive or a tenants rights organization. But that spirit of shared interests, of the Gandhian notion that all men are brothers, is today in vanishingly short supply, exacerbated by a digital culture that is atomizing by design.

A central challenge, then, of political organizing in the modern age is that the incentives of the internet are all but diametrically opposed to those of movement building. Online, we are shackled within the smooth-walled prison of the present: a digital realm calibrated toward name-calling, zero-sum binaries, and dopamine hits doled out for the pithy and self-righteous bonbons we fire off with our thumbs. Here are slick words and slogans that obliterate texture and render the knotted complexity of life in clean lines and angles etched by pure ideology, where the theoretical and abstract reign supreme. The more absolutist our rhetoric becomes, the more our public utterances go viral. A movement, by contrast, is built one person at a time, and requires everything that the internet bats away: ambiguity, empathy, the willingness to sit in discomfort as we wait for the bonds of interpersonal trust to emerge and deepen. The success of a political movement depends not on ideological purity, but on results: the accumulation of power to effect change.

Faced with a regime in lockstep with Israel’s goal of relocating the entire population of Gaza, we simply don’t have the luxury of indulging in purity tests. Instead, we should stand shoulder to shoulder with all those who want to see an end to the starvation and the killing. At the same time, we ought to acknowledge complexity where it exists: that antisemitism—not anti-Zionism, but good old-fashioned Jew hatred—is demonstrably on the rise, and that we can raise our voices in opposition to this grotesquery without letting it knock us off the course of Palestinian solidarity.

And as I’ve written before, we should reject purity politics and sloganeering in domestic politics as well. Overcoming the terrifying tide of authoritarianism, with its warrantless arrests and violent deportations, will require a movement that can appeal to disillusioned swing voters, who represent the broad, persuadable middle of the electorate. Let us lead, then, not only with moral clarity, but with openheartedness and humility. Calling Trump supporters “MAGAts” does nothing but make us smaller.

Of course, the temptation to train our rage on those we perceive to be complicit in the Trump agenda is only human. In Stride Toward Freedom, an account of the 1955-1956 Montgomery bus boycott, Martin Luther King, Jr., describes several moments in which his anger got the best of him. Small wonder, given that his house, and those of several of his associates, had recently been bombed. Nevertheless, he remained steadfast in his belief that only through the practice of agape, or Christian love, could justice be made manifest. For those left of center, we might begin by mending the breach between leftists and liberals. As the philosopher and organizer Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò wrote a few years ago, “at some point you should decide whether you will accept the discipline imposed by your material objectives and commitments or the ‘discipline’ imposed by your resentments. The ruling classes would like nothing more than to choose for you.”

The best way that I know to achieve this—to be guided by material objectives rather than by resentment—is to rededicate ourselves to heart work. At a time when many of us feel powerless in the face of an endless barrage of existential crises, we can choose to practice love and kindness in our daily lives, and, in particular, in how we interact with those with whom we disagree. It’s one of the few things over which we have total control in this mad, mad world.

Recent & Current Reading:

Melting Point, by Rachel Cockerell

Stolen Air (Selected Poems of Osip Mandelstam), translated by Christian Wiman

I Saw Ramallah, by Mourid Barghouti

Stride Toward Freedom, by Martin Luther King, Jr.

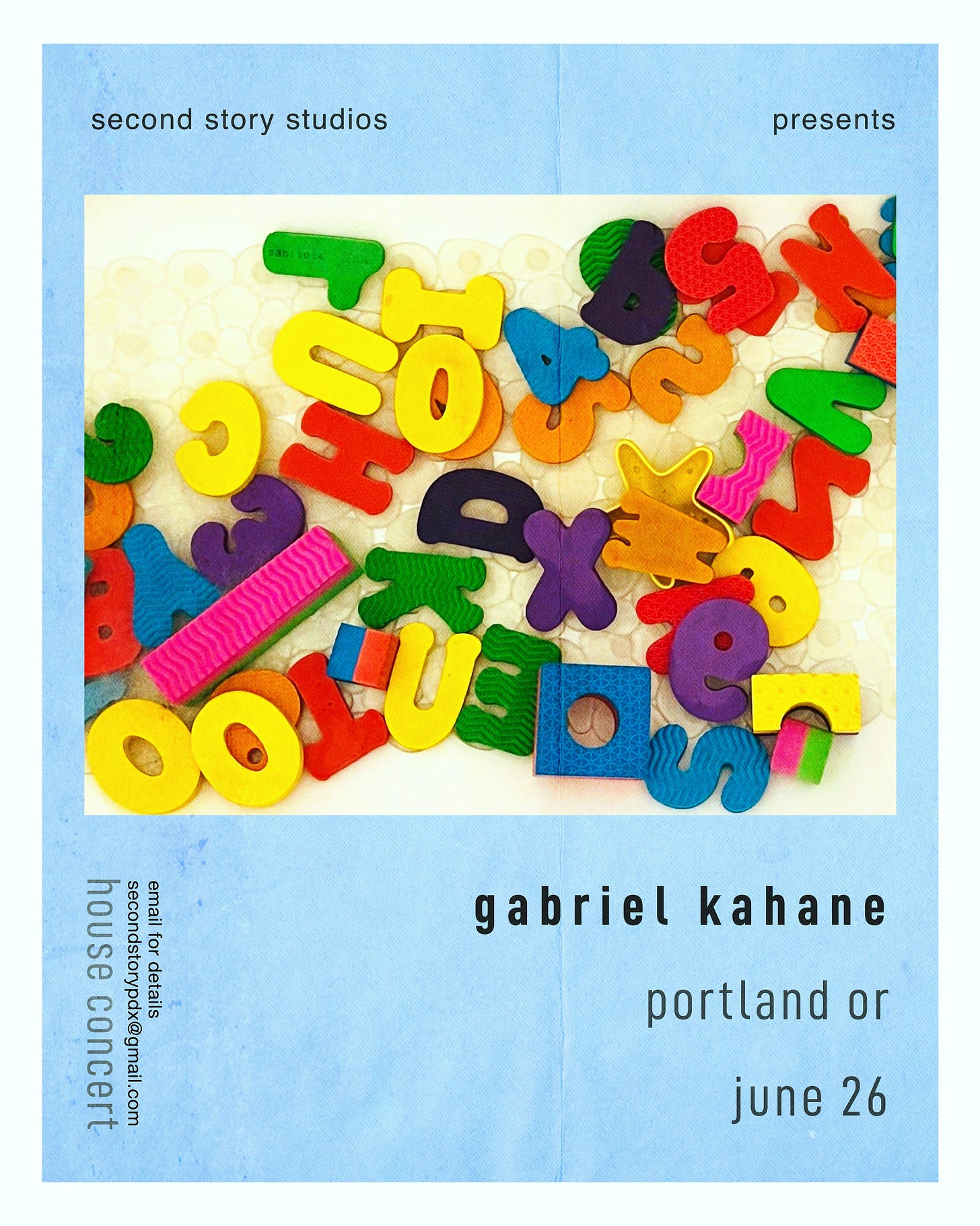

On Friday night, I conduct the Sarasota Festival Orchestra in a performance of my piano concerto, Heirloom, with my father as soloist. Next Thursday, June 26, I’m doing a solo house concert back in Portland. Some tickets remain; send an email here to purchase them. As always, thank you for reading, and, to those of you who are paid subscribers, for your crucial support in making this newsletter a reality. If you’ve not already done so, consider upgrading today.

I think the difference between one state and two state progressives is more than one of degree, so perhaps they're not the natural/potential allies you think. If one thinks Israel per se is a settler colonial state, then aligning with 2 state factions may feel akin to aligning with someone arguing that the creation of a black Zimbabwe alongside a white Rhodesia would have been the best solution to that conflict. There's a large conceptual gap there. That doesn't mean, as you've said before, that alliances can't be forged, especially over short term goals. Toleration is often a virtue. But I'm not convinced that the differences are primarily to do with ideological posturing or virtue signalling. The longer term material objectives, as Taiwo puts it, are quite different.

Thank you for capturing a lot of what I (a Sephardic American Jew with family in Israel) have been feeling. You’re absolutely right that Zionist has become a slur that us Jews on the left are trying to figure out how to relate to. It always tingles the back of my neck to hear it used as an absolutist insult but given its modern definition - and my politics - it’s been hard to articulate why. This piece helps, so again thank you!