My new album, Heirloom, featuring a piano concerto I wrote for my father, is now available for pre-order via Bandcamp. I’m also headed out on tour this fall. My tour dates are here.

Today, Nonesuch Records releases “Where are the Arms,” a song of mine that was first recorded and released as the title track of my sophomore LP back in 2011. Its inclusion on Heirloom, in a new arrangement with chamber orchestra, was not arbitrary: the song figures heavily in the concerto’s first movement, titled “Guitars in the Attic.” (You can read more about how the song relates to the piece here.) At any rate, I thought this would be a good time to delve more deeply, for those who are interested, into the dark art of arranging.

For the purposes of this essay, I’m thinking of arranging in a limited way: the application of western classical instruments to popular song. There are, of course, many other modes of arranging. Recently, I’ve been obsessed, for example, by the guitar-heavy production on Blue Reminder, the latest album from Hand Habits; by Kenny Segal’s hallucinatory work with beats and samples on Maps, an album he made in collaboration with the m.c. billy woods; and, as I wrote a few weeks ago, by Ole Morten Vågan’s kaleidoscopic big band charts for Jason Moran on Go To Your North. Each of these aesthetic worlds is deserving of its own essay—some other time.

As composers, the language of visual art has long served as a shorthand. We speak of color and line in much the way a painter might. If the song is a pencil sketch, it becomes a painting when a string or brass arrangement is added. A high violin melody might radiate bright yellow, while a trombone choir could suggest a rich smear of blue and purple. Or perhaps you’d prefer an epicurean metaphor: the song is a dish of smashed potatoes; the arrangement finds those spuds adorned with chopped herbs, a glug of olive oil, and a generous squeeze of lemon.

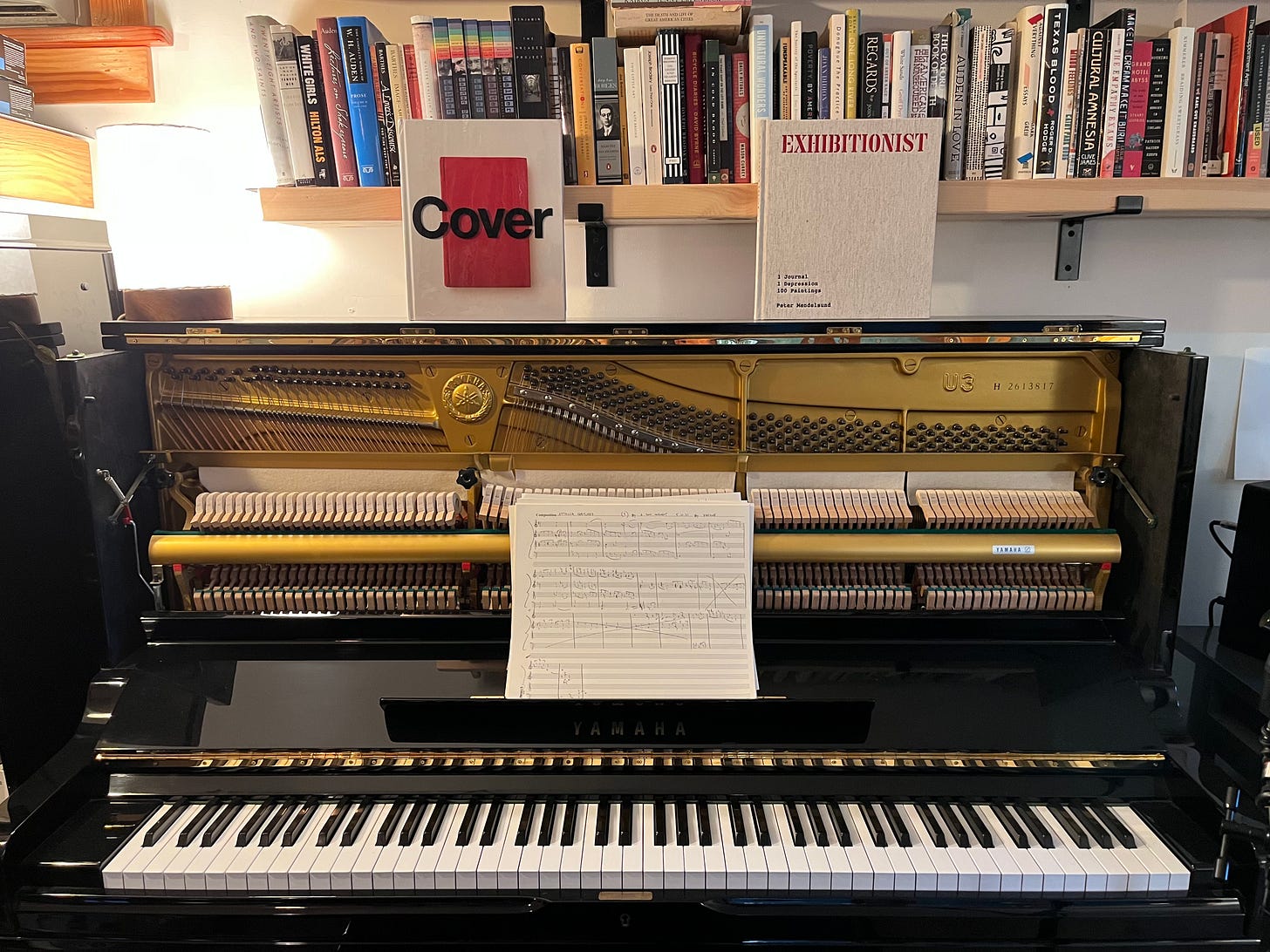

When I was younger, I wrote arrangements longhand, sometimes taking the subway from Brooklyn up to the Hungarian Pastry Shoppe at 110th St. and Amsterdam in Manhattan, across from St. John the Divine. Back then, it was one of the few places in the city that didn’t have a stereo, so my inner ear didn’t have to compete with the Yeah Yeah Yeahs or Kelly Clarkson. After ordering coffee and a viciously unhealthy Mitteleuropean treat, I’d ensconce myself behind one of the cafe’s chewed up wooden tables, while throngs of grad students and neighborhood lifers studied for exams or hacked away at the day’s crossword puzzle. Arranging by hand was painstaking, but it afforded pleasures both tactile and visual. As I added woodwinds above or strings below, I could witness a melody being sewn, gradually, into new, bespoke garments. And there was the satisfaction, too, of having filled an 11x17 page of manuscript paper with pale graphite runes, then moving onto the next. Ah, youth!1

There are some arranging truisms that nevertheless bear repetition: stay out of the way of the vocal line. Be mindful not to fill every empty musical space. Think about how the listener is digesting the words of the song, and whether the gesture that follows a lyric functions as subtext, irony, amplification, or contradiction. Less is generally more; remember that the “exit” of an instrument not only draws the listener’s attention back to the vocal, but also creates anticipation for its return. Rarely does a great arrangement rescue a song from its fundamental mediocrity, but a bad arrangement can ruin a great song. Lastly, the best arrangements never call attention to themselves — except when they do.

My favorite charts are not simply a collection of beautiful gestures, but architectural rigorous unto themselves. When you study an excellent arrangement, it reveals itself to contain the same degree of inevitability we expect in our favorite pieces of music, even though these ornamental elements are largely relegated to the background.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of arranging gestures: accents and undercurrents. An accent is the flourish that comes at the end of the phrase, an end table, a vase, or an ornamental lamp. It’s often there to create musical interest while the vocalist rests. An undercurrent, on the other hand, is a texture that enters and continues under the vocal. (Think of a stratospheric, slow-moving violin line on a Motown record, or I dunno, an area rug.) The challenge with an undercurrent is that it must walk the line between musical interest and unobtrusiveness. Again, we never want to pull the listener’s ear away from the melody.

Sam Amidon’s recording of the folksong “Saro,” from his 2007 album, All Is Well, contains accents and undercurrents. (All of the charts on that record were written by my friend and colleague, Nico Muhly.) Part of what makes the arrangement effective is the compositional clarity in what Nico is doing. There are four gestures: first, there’s a laconic duet between bassoon and trombone, with a descent in the latter instrument that recalls the trumpet backgrounds in Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline,” but slowed down to a glacial tempo.

In an interlude, flute and clarinet enter with child-like arpeggios outlining the tonic against the guitar’s subdominant. The resulting sonority is a classic minimalist wash, basically tiramisu in musical form. As the second verse begins, violin and viola enter, pulsing quarter notes with little melodic movement. The gesture evolves just slowly enough as to be almost imperceptible beneath Sam’s vocal line, the two voices moving step-wise, often leaning into aching suspensions that amplify the song’s melancholy. Once Sam drops out, strings become the foreground, but the texture remains elegantly simple. In the final refrain, a lone French horn recalls the trombone riff, and then, in an instrumental coda, we have low, guttural trills from the strings: a chorus of whispered regrets. Like all great arrangements, Muhly’s chart for “Saro” keeps the lyric front and center. But with his precise and delicate instrumental writing, Nico manages to enhance the track’s emotional impact. It is devastatingly beautiful.

I mentioned above the value of an “exit,” by which I mean the departure of an instrument from the texture. There’s something about introducing a new color, then having it disappear, that not only refreshes the ear, but creates the expectation of—and delight in—its return.

In “The Predatory Wasp of the Palisades Is Out to Get Us!” from his 2005 album Illinois, Sufjan Stevens demonstrates just how powerful this approach can be. Where the verses are spare—just a single guitar accompanying the vocal, with dirt simple background vocals entering on the pre-chorus—the interludes introduce a variety of color: here, a scrum of out-of-tune oboes, pointillistic, insectile, urgent; there, the naive, unison descent of accordion and trumpet. When, two-and-a-half minutes in, the chorus finally hits, voices and woodwinds collide, and the resulting texture is one of unmediated ecstasy. In a brilliant essay published in The Guardian eighteen years ago, Nico Muhly wrote, of this song:

This juncture (between "genres", between people, between styles) is best achieved when it bypasses thought and operates through the nervous system, the spine, and the fingertips. It is this automatic, synapsey music that Stevens accesses with these oboe interludes…

Sufjan and I were fairly close from around 2007 until 2010. During that time, I got to witness his process up close, and contributed some of the string arrangements to his 2010 album, The Age of Adz, which signaled a shift away from the baroque folk music for which he’d become known, and toward an even more maximalist sound world, now infused with burbling synthesizers and drum machines. To say that I learned a lot from him would be an understatement. One of the lessons I drew from my time working with Sufjan was to appreciate the difference between maximalism and clutter. When I presented him with initial drafts of my arrangements, he said bluntly, “why would you have the violins play that [melody] there, it’s going to step on the vocal!” And yet he in his own arrangements, he could somehow add layer upon layer of color and texture without it ever seeming too much.

Where many arrangers use western classical instruments as glorified synth pads, asking players to hold long notes ad nauseam—what we, in the industry, disparagingly call “footballs,” because of the whole note’s resemblance to the pigskin—Shara Nova, a.k.a. My Brightest Diamond, has other ideas. On “We Added It Up,” the opening cut from her brilliant 2011 album All Things Will Unwind, she deploys the six-member new music ensemble yMusic to stunning effect, their interjections as witty and irresistible as Katharine Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby. When, in the refrain, the ensemble finally relaxes into sustained chords, the textural shift alone carries emotional weight. Shara has a rare ability to showcase an instrumentalist’s virtuosity while not only making it seem effortless, but necessary—nothing is arbitrary or ostentatious. It’s frankly unfair that someone with the voice of an angel should also be this adept at coaxing gold from a piccolo.

I first performed the arrangement of “Where are the Arms” that appears on Heirloom with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra back in November of 2023. For the album, which was tracked in May of 2024, the Knights and I recorded the orchestra and guitar live in two takes; I sang the vocal back in my studio in Portland a few months later. It’s a song that most obviously belongs to a lineage of post-heartbreak pep talks. But I think it’s also a song that concerns forgiveness. As our nation grapples this week with another constellation of self-inflicted tragedies, the possibility of forgiveness, and of reconciliation, has been on my mind.

Suffice it to say: love and confrontation are not mutually exclusive. There is no question in my mind that aggressive, confrontational, and nonviolent action must be taken to combat authoritarianism. But that confrontation can play out with or without spiritual discipline. Where some believe that the hate and vitriol emanating from one political camp justifies the same outpouring of bile from another, I remain dogged in my belief that spiritual hardiness—the insistence on loving our enemies—can and must undergird the urgent work of repairing our democracy. Okay, enough of my soapbox. Go have a listen to “Where are the Arms.”

As always, thank you for reading, and for your support. If you have the means, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription, which allows me to carve out the time to write. If not, liking, commenting, and sharing are nearly as helpful! If you’ve been waiting to pre-order Heirloom, now’s a great time to do so. About forty limited edition prints, which accompany pre-orders, remain.

I suppose this wave of self-indulgent nostalgia is the byproduct of re-releasing a song I wrote sixteen years ago! I’ll stop.

Ah . . . the Hungarian Pastry Shoppe! One of my absolute favorite places in NY. Sure, the pastry is tasty, but there’s something even more special about the place. I can’t quite figure out why which may be the reason I am so taken by it.

Since the father of my children and I met at the Bar 717 Ranch and we live in Portland, and your music is swoon worthy, you have my attention. Love this dive into the arranging arts. Thank you.