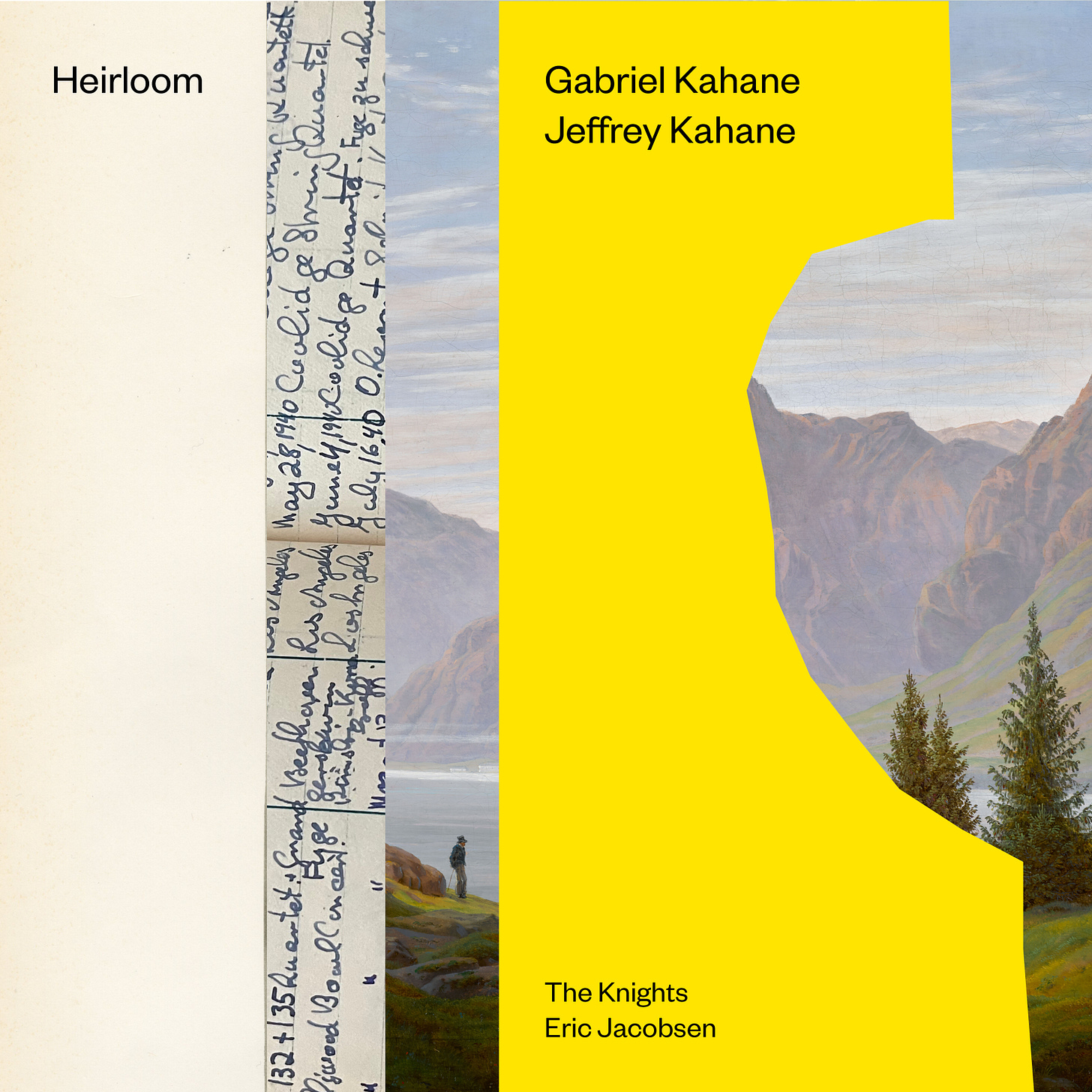

My new album, Heirloom, featuring a piano concerto I wrote for my father, is now available for pre-order via Bandcamp. I’m also headed out on tour this fall. My tour dates are here.

1.

In 1995, a Stanford doctoral student conducted an experiment in which she and her research assistants set up a display of jams at a supermarket in Menlo Park. Every few hours, they changed the number of jams available, alternating between selections of six and twenty-four flavors. Most of the findings were unremarkable: 60% of those who entered the store were drawn to the larger display, compared with 40% who visited the smaller one. While all shoppers sampled, on average, two jams, 30% of those who approached the more modest display made a purchase. The real revelation? Those who visited the larger display bought jam only 3% of the time.

This study—published in 2000 and led by Dr. Sheena Iyenger, who is now a professor at Columbia Business School—is a perfect illustration of choice paralysis. People tend to be attracted, in the abstract, to having many choices. But in practice, too many choices can be paralyzing. I was reminded of the jam study, when, after sharing my recent essay about Spotify, a number of readers asked some version of the following question:

I know Spotify is awful—I use it reluctantly because the catalog is amazing—are any of the other streaming services better for musicians?

If “better” is understood to be a measure of royalty rates alone, then the answer is “yes.” Apple and Tidal pay marginally more than Spotify. Moreover, neither of those competitors is trumpeting its work in the war profiteering sector, as Spotify CEO Daniel Ek has done. But if we move beyond matters of economics, the answer is more complicated.

Today, Spotify, Apple, and Tidal each boast more than 100 million tracks. It would take roughly 570 years to listen to the entire catalog on any one of these services. Rather than comparing royalty rates—all paltry enough to constitute a distinction without a difference—perhaps we should instead be asking: what kind of listeners do we become when we have access to tens of millions of songs? Do we listen more deeply? Or are we more likely to sample a good deal of music superficially, while listening to very little of it with focus and intention? In other words, do we sample several jams and walk out of the store empty-handed?

More than leading to choice paralysis, instant access to a nearly infinite sonic library has reshaped—if not debased—music’s role in our lives. “An interface that defaults to mood-based playlists,” I argued recently, implies that “artists—and the music they make—are only valuable as interchangeable cogs in a sonic mood stabilizer…” Invoking the ghost of Marshall McLuhan, I continued:

The “message” of a streaming service’s “autoplay” function is that, as a matter of course, you should always be listening to something, and that music is neither sacred nor worthy of a listener’s undivided attention.

The gulf between the “message” of the autoplay function, on the one hand, and that of the tactile experience of playing a record on a turntable, on the other, is vast. With an LP, there is the multi-step process of removing the disc from its sleeve, placing it on the platter, and dropping the needle. By the time this ritual has been completed, we’ve made a small but tangible investment of physical labor. Insignificant as they may seem, these physical actions incentivize us to listen through, if only to the end of the side. More than that, once a record is on the platter, there is a physical cost to changing our mind, inasmuch as we have to run the ritual in reverse before choosing another album to play. (The Ikea Effect, a 2011 working paper, demonstrated that when we labor over the construction of an object, it becomes more valuable to us.)

Streaming offers no such friction. Nor does it provide us with an opportunity to invest, physically or monetarily, in what it is we’re listening to. Without skin in the game, we have little incentive to stick with a song we find dissonant or even momentarily confounding. If you’ve ever had the experience of scrolling through a streaming library and either a) found yourself skipping songs because you fear that you’re listening to the wrong music, or b) become so overwhelmed that you give up entirely, then you, my friend, may be suffering from choice paralysis.

2.

There is also the vexed matter of active versus passive listening. Perhaps you’re the type who spins vintage Coltrane LPs, concentrating furiously on a Paul Chambers bass line while nursing a Negroni. Or you might stream Olivia Rodrigo on your bus commute, dozing on and off, creating a universe within the comforting confines of a good pair of headphones—sometimes headphones also denote a boundary of physical safety. Others may hum along to Sam Amidon while fiddling with excel spreadsheets, or listen to a Gabriella Smith string quartet while pricing books. I don’t intend to make a moral argument about the attention we bring as listeners. More than that, the internet did not create passive music listening, whose lineage runs through the Sony Walkman, and the radio before it.

But it is worth commenting, at least briefly, on the ways in which music operates on the senses differently than the other arts, and how that may alter our relationship to it. Where reading requires a combination of eye movement and cognitive processing, music, strictly speaking, can be experienced, albeit superficially, without any active engagement. Plenty of people listen to music while they write or study. But you never hear anyone claim that they read a book while they write, or look at paintings while they cram for a math test. That’s because these tasks require our eyes as well as some degree of cognitive activity.

As Liz Pelly details in Mood Machine, Spotify was a trailblazer in recognizing that its users often listened to music passively. Over time, the company transformed its business model to encourage more of this passive listening, steering users toward inoffensive playlists that would keep users in the app. Again, I don’t wish to moralize. But if you’re streaming music in the background while engaged in another demanding mental task, I would argue that you’re not really listening — you’re just hearing. And even if you’re not actively participating in Spotify’s race to the bottom with Coastal Grandma or Chill Vibes playlists, by subscribing to the service, you are subsidizing the deterioration of listening habits among millions of others, for whom music has largely become aural wallpaper.

What does all this mean for the dignity of an artist whose work has been shunted to the background? If we are unwilling to offer direct compensation for her labor—which, itself, is increasingly obscured by the digitization, reproduction, and effortless transmission of music—do we not owe her our attention? More than that, do we not owe it to ourselves to pay attention to the music we’re listening to? You wouldn’t read a Toni Morrison novel “in the background,” so why would you relegate a beloved songwriter to that status? If we are to derive uplift or edification from art, surely some degree of attention and intention is required.

And yet technology companies—and the culture more broadly—have trained us to feel a sense of entitlement toward instant access to vast stores of music. There is a chicken/egg phenomenon at work here: if we listen to music all the time, as Spotify would have us do—while we garden, study, do dishes—we expect it to be free. For scarcity, rather than abundance, confers value. And if it’s free, why wouldn’t we listen all the time?

A few months ago, I gave up streaming altogether. After letting my Spotify account lie dormant for several years, I canceled it upon learning that Daniel Ek had thrown a lavish brunch for Trump (caviar, crab claws, espresso martini conveyor belt), while donating $150,000 to the President’s inauguration fund. (Earlier, I’d stopped using the service when the company’s “ghost artist” practices were exposed.) For a time, I had switched to Tidal, the app preferred by many professional musicians. But after reading Mood Machine, I realized that I couldn’t expect people to purchase my albums if I didn’t buy theirs. More than that, I felt that the quality of my listening had declined since I’d begun streaming music. I seldom listened to an album all the way through, let alone more than once. The temptation of the catalog, the proximity to so many other choices, made it difficult to focus on whatever I was listening to. I was at the large jam display, except that instead of twenty-four options, I had twenty-four million, and another twenty-four million on top of that. Finally, I canceled my Tidal account, and returned to listening habits I’d first developed as a teenager.

3.

Growing up in Santa Rosa, California, I bamboozled my way into a job at a comic book store, betting the owner that I could beat him in a game of chess, and insisting that he employ me if I won. (He didn’t know I was a nationally-ranked player, and I didn’t offer that information before we sat down to play. Shame on me.) Vanquished on the chessboard, he reluctantly put me to work Friday and Sunday afternoons. Every other week, I’d cash my modest paycheck and visit The Last Record Store, which was conveniently located across the street from my high school. I’d pick up an album or two, take home my spoils and head for my bedroom, where I’d listen on repeat to whatever I’d bought. Sometimes I didn’t enjoy what I heard on the first pass. But I’d spent fifteen bucks on the damn thing, so I was incentivized to learn to love it. More often than not, that’s what happened.

Thirty years later, I am again listening, closely and repeatedly, to records I own. I have more disposable income than I did as a teenager, but I’m not buying albums left and right. Instead, I aim to purchase only as many records as I can listen to meaningfully. (Years ago, the legendary record executive Bob Hurwitz told me that as a college student, he had a policy that he could own no more than 50 LPs at a time: one in, one out. While the collector in me bristles slightly, I love this idea.)

For me, reviving older listening habits is a way to demonstrate respect for the artists I admire. To purchase an album is to acknowledge the labor and resources that went into making it. By listening to it actively and repeatedly, I also offer respect through attention. A few months into this renaissance, I find myself unshackled from the FOMO that once paralyzed me when I streamed. In a world oversaturated with information, giving up access to our sonic “Library of Babel,” it turns out, is not limiting, but liberating.

One of the records I’ve fallen for hardest since implementing my new/old listening regimen is Jason Moran’s Go To Your North, a collaboration with the Trondheim Jazz Orchestra and bassist/arranger Ole Morten Vågan. The album comprises new arrangements of extant works from Moran’s catalog, and the first cut, “Foot Under Foot,” continues to melt my brain after seven or eight spins. The track opens with an initial full-band statement of the tune—a deft, winding post-bop melody that turns in on itself repeatedly, shifting between duple and triple meter—before disintegrating into a texture of craggy, moonscape fragments. These gradually reconstitute themselves as a tenor saxophone solo, featuring the inventive and assured improviser Karl Hjalmar Nyberg. Spasmodic, knife-like gestures give way to spacious lines as bass and drums gather steam, and a blazingly fast swing tempo takes hold, with Moran laying out to make space for Nyberg’s torrents of sixteenth notes. Once the chordless trio has found its groove, the piano enters with muddy clusters, and seconds later, a horn section enters, siren-like, a keening shock that echoes Nyberg’s altissimo exhortations. (This moment makes my hair stand on end every time I hear it.) There’s another full band statement, and then the atmosphere shifts suddenly, like a freak sixty degree drop in temperature on a late fall day in the Dakotas.

Here, now, is a lone trumpet (Eivind Lønning), exploring the limits of the instrument through ghastly multiphonics. Another solo follows, beginning dirge-like before accelerating to the original tempo. By the time Moran takes center stage, entering with glassy triads threaded against lilting bass and drums, we’ve seen the earth complete at least one revolution around the sun, all in the space of seven minutes. It’s my favorite kind of music: gritty and regal; shocking yet inevitable. Each time I listen, something new comes to light. Here, the way the horn backgrounds that haunt the trumpet solo recall the main tune, but slowed down to a sloth’s tempo. There, the sumptuous bass tone, or the mercurial color of the ride cymbal.

As with most of Moran’s post-Blue Note catalog, Go To Your North is not available on streaming services. I texted Jason to ask him for his thoughts on the streaming economy. Here’s a condensed version of what he had to say:

At this point… I’m funding the projects I want to make. I have a value that I place on my work—in the ‘90s, CDs were often $15-$20. The price—emotional and financial—for artists to make music, is calculable… I have no trust in the streaming system. So why would I send my babies, my recordings, to the plantation?

Moran makes music that rewards deep, repeated listening. It makes perfect sense to me that he would reject streaming services, which, as I have argued, are engineered to facilitate the opposite: surface level background listening. And while his invocation of “the plantation” might seem provocative, I don’t think he’s wrong. The streaming economy instantiates a kind of wage theft. It’s not chattel slavery, but it unquestionably devalues the labor of all those who toil over creative work. If we commit to listening intentionally, we may listen less. But in so doing, we might discover that we actually can afford to pay for the music we enjoy, offering dignity and respect to artists twice over: first, in granting them our attention, and second, in compensating them fairly for their work. Perhaps, in the end, six jams can keep us sated.

As always, thank you for reading, and for your support. If you have the means, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription, which allows me to carve out the time to write. If not, liking, commenting, and sharing are nearly as helpful! September 5th is Bandcamp Friday, which means that the company is waiving its revenue share for twenty-four hours. If you’ve been waiting to pre-order Heirloom, now’s a great time to do so. About fifty limited edition prints, which accompany pre-orders, remain.

That Jason Moran album is so huge and joyful, and very different from his previous classic only a year or so earlier. One thing that got me into Bandcamp was the realization that it was my only way to get at Moran's recent work.

brilliant essay with lots to chew on. For me, Passive listening has its place. I bailed on streaming recently, and when i need some background music, i turn to internet radio; NTS, Aquarium Drunkard; Lot Radio, old episodes of New Sounds/WQXR. It’s a joyful experience having music curated by actual human beings, not algorithms. And in a format where i give up all control except what DJ is delivering it and what time their set is.

Most of the time what i hear is unfamiliar, but when something familiar comes up i feel an immediate connection to the person who selected it, and/or to my younger self, and/or to friends who showed me the music. The arts are a community building project and intentional engagement reinforces this, while streaming isolates us from that.