the perfect playlist

On Liz Pelly's 'Mood Machine' and the ethics of streaming

The changes and disruptions that an evolving technology repeatedly caused in modern life were accepted as given or inevitable simply because no one bothered to ask whether there were other possibilities.

Langdon Winner, Autonomous Technology (1978)

What is music for? Why do we listen? What does it mean to have instant access to infinitely reproducible, digital versions of tens of millions of songs, stripped of context and jumbled into machine-generated playlists? How are we, and our values, changed by those devices that allow us to listen to music, often passively, as we go about our days, tending our gardens, driving to the dentist, or sleepwalking through airports? And what becomes of artists—with respect to their material, aesthetic, and spiritual sustenance—in such a world?

These questions were on my mind as I read Liz Pelly’s absorbing and essential book, Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist, which traces the streaming giant’s evolution from start-up ad agency to global behemoth, a company whose endless torrents of inoffensive bedroom pop and soporific piano playlists are designed to suspend listeners in a state of quasi-catatonia. Pelly draws a meticulous and grim portrait of a firm, which, driven by profit, has made the exploitation of musicians’ labor central to its economic logic, while pushing listeners and musicians alike toward a banal aesthetic that serves the company’s bottom line. Crucially, the economic devaluation of recorded music and the flattening of aesthetics are not discrete phenomena: the effort to keep listeners soothed and sedated through personalized playlists stocked with cheaper, mass-produced music was a market-tested strategy designed to maximize Spotify’s profitability.

Few among us would steal an LP from a merch table. Yet we blithely stream music through a platform whose business practices have had catastrophic consequences for artists and listeners alike. Why is this the case? And how did we get here?

Spotify was founded in Sweden in 2006 as an ad agency. It settled on music streaming as a means of driving traffic because audio files were smaller than video files. For a time, the company was heralded as an industry godsend, creating a new source of revenue for the major labels, which had been hobbled by the piracy crisis of the early aughts. In 2012, having made in-roads in the U.S. market, the company commissioned a study which found that “the vast majority of its users were not coming to Spotify for specific artists and albums.” Instead, Pelly writes, “they just needed something—anything—to soundtrack their days. They were coming for a passive experience, where they could press one button and hear some appropriate music.”

Thus, Spotify pivoted toward “lean-back listeners,” users who sought unceasing sonic accompaniment to their every activity, and were now guided toward mood-based playlists rather than specific albums or artists. By the mid-2010s, streaming revenue had put the major labels—which, to this day, enjoy secretive financial arrangements with Spotify—back in the black. But Spotify was still hemorrhaging money. “So its music programming execs tried something new,” writes Pelly.

[T]hey developed a scheme to lower royalty costs by populating the most-followed mood playlists with low-budget filler tracks; stock music from background music studios to fit certain moods and genres, licensed by Spotify under… special, cheaper deal terms. The songs were often made by anonymous session musicians…[who] would crank out dozens of tracks at a time, assigning them one-off monikers.

This low-budget filler came to be known as “perfect fit content,” or PFC, which, by 2023, had come to dominate at least a hundred official playlists, as editors were pressured to swap out songs by real musicians in favor of those by “ghost artists” working for subcontractors. The Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, writes Pelly, found that “around twenty songwriters were behind over five hundred artist names, and that between them, Spotify was flooded with thousands of their tracks streamed millions of times.” And it gets worse.

Spotify calculates royalties on a pro rata basis rather than per stream, which means that “ghost artists” rob real artists twice over: first, by pushing them off of playlists, and second, by diluting their remaining “streamshare.” The more “ghost artists” are streamed, the less value a stream has for a real one. According to Pelly, the catalog of Epidemic Sound, a major players in the “ghost artist” market, receives 40 million streams—per day.

As Spotify saw its profits increase through its PFC/”ghost artist” scheme, it adapted its design to further highlight and prioritize mood-based playlists, a gambit intended to create more “lean-back listeners.” This transformation, which made individual artists and albums more difficult to find, sacrificed user experience for company profit, a process described by the writer Cory Doctorow as “enshittification.”

Along the way, as it disseminated endless personalized playlists calibrated to imprison users in a silo of passive listening, the company developed an inoffensive, chilled out, lab-tested aesthetic: what the New York Times would dub “spotifycore.” And it wasn’t just listeners who paid the price. For some musicians, writes Pelly,

chill-vibes playlists were becoming new goalposts to hit in their songwriting. But more often, what happened was that the mellowest moments in their discographies were unexpectedly plucked—by editors or algorithms—for the purposes of a mood mix, taking on new life as playlist fodder. What was playlist friendly was proving often to just be what was most smoothed out.1

Spotify’s practice of highlighting an artist’s simplest songs and burying the rest echoes the logic of private equity: buying an asset, stripping it for parts, and discarding the rest, often at the expense of workers’ livelihoods. For artists outside the mainstream, this causes a ripple effect of harm. Before its pivot toward “perfect fit content,” Spotify was often an effective discovery tool. Its earlier algorithms sought to match music to users, which meant that more adventurous listeners would discover more adventurous artists. But with the aggressive lurch toward the sanded down “spotifycore” aesthetic, it’s become much more difficult for niche audiences and artists to find each other. And even as it has made their music more difficult to discover, Spotify has invented new ways to extract money from artists.

The Spotify for Artists app (S4A) presents users with a dashboard that gives artists the illusion of agency, while seducing them into paying for promotion of their music. When they opt into “Discovery Mode,” one of the core features marketed by S4A, musicians receive a better chance of landing on algorithmic playlists in return for a 30 percent cut of their already paltry royalties: instead of averaging $0.0035 per stream, they’ll make $0.0024.23 Often likened to the illegal Payola radio schemes of the 1950s, “Discovery Mode” creates a “damned if you do/damned if you don’t” race to the bottom for artists and independent labels alike, which feel pressured to participate for the sake of visibility, even as royalty payments shrink. Meanwhile, the pay-to-play aspect remains hidden from the user, leaving her unaware of whether a song she is hearing is, in essence, an advertisement.

As Pelly notes, these arrangements turn the popular notion of the “creator economy” on its head. Unlike the models that drive Patreon or Substack, “[Spotify’s] own ‘creator’ tools don’t involve fans paying artists, but rather, artists paying the company.” And in the same way that the Spotify app flattens and fragments musicians, the Spotify For Artists app flattens and dehumanizes audiences. Inundated by statistics, an artist sees her public gamified, transformed into something distant, abstract, digitized. By reducing audiences to mere numbers, the app obscures the ineffable exchange that occurs in live performance between a performer and her public, one that can be as meaningful in a room of fifty as within a stadium of thousands. What does this incentive structure do to an artist’s creative instincts?

As we consider the ways in which streaming services have changed our relationship to music, Marshall McLuhan’s evergreen observation that “the medium is the message” offers a useful framework. The “message” of an interface that defaults to mood-based playlists is that artists—and the music they make—are only valuable as interchangeable cogs in a sonic mood stabilizer; songs or artists with conflicting, challenging, or dynamic emotional valences need not apply. The “message” of a streaming service’s “autoplay” function is that, as a matter of course, you should always be listening to something, and that music is neither sacred nor worthy of a listener’s undivided attention. Finally, the “message” of a platform that presents to its users fake artists with invented biographies is that deception is acceptable, so long as it serves the profit motive of the company.

In many sectors of the economy, it can be difficult to consume products ethically. But when it comes to the music business, we have choices. Platforms like Bandcamp permit listeners to pay artists directly. Yet the majority of us continue to stream, exploiting the labor of musicians we claim to love, while participating in the degradation of music into a hollowed out commodity that serves as so much aural wallpaper.

Perhaps our comfort with the status quo stems from our unconscious embrace of “inevitablism,” a phenomenon described by Shoshana Zuboff in her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism:

Every doctrine of inevitability carries a weaponized virus of moral nihilism programmed to target human agency and delete resistance and creativity from the text of human possibility. Inevitability rhetoric is a cunning fraud designed to render us helpless and passive in the face of implacable forces that are and must always be indifferent to the merely human. This is the world of the robotized interface, where technologies work their will, resolutely protecting power from challenge.

At a time when many feel powerless to resist the seemingly inexorable march of capitalism and fascism, aided and abetted by big tech, the music economy presents an opportunity for meaningful action, individual and collective. If art provides a theater in which to document and resist repression, then supporting those who make it ought to be viewed as an unequivocally benevolent act. Beyond remunerating individual artists directly, there are nationalized efforts underway to better compensate musicians en masse. These are described in Pelly’s forward-looking conclusion, which chronicles the rapid momentum of the new music labor movement, instantiated by organizations like the United Musicians and Allied Workers (UMAW), the Music Workers Alliance (MWA), and a flagship piece of legislation, the Living Wages for Musicians Act, which aims to “create a new royalty from streaming music that would bypass existing contracts, and go directly from platforms to artists," with the goal of paying artists an annual living wage.

My plea to you, reader, is to boycott Spotify. Instead of streaming, allocate a monthly budget, within your means, for purchasing records. If you’re like me, you’ll find that the quality, depth, and focus of your listening will improve dramatically. And if you’re old enough, you’ll remember what it was like to take home a new recording and listen to it obsessively. It might not grab you the first time. But because of the financial investment you’ve made, you’ll likely give it a second chance. And just maybe, on the third, fourth, or seventh listen, you’ll have fallen in love with something new.

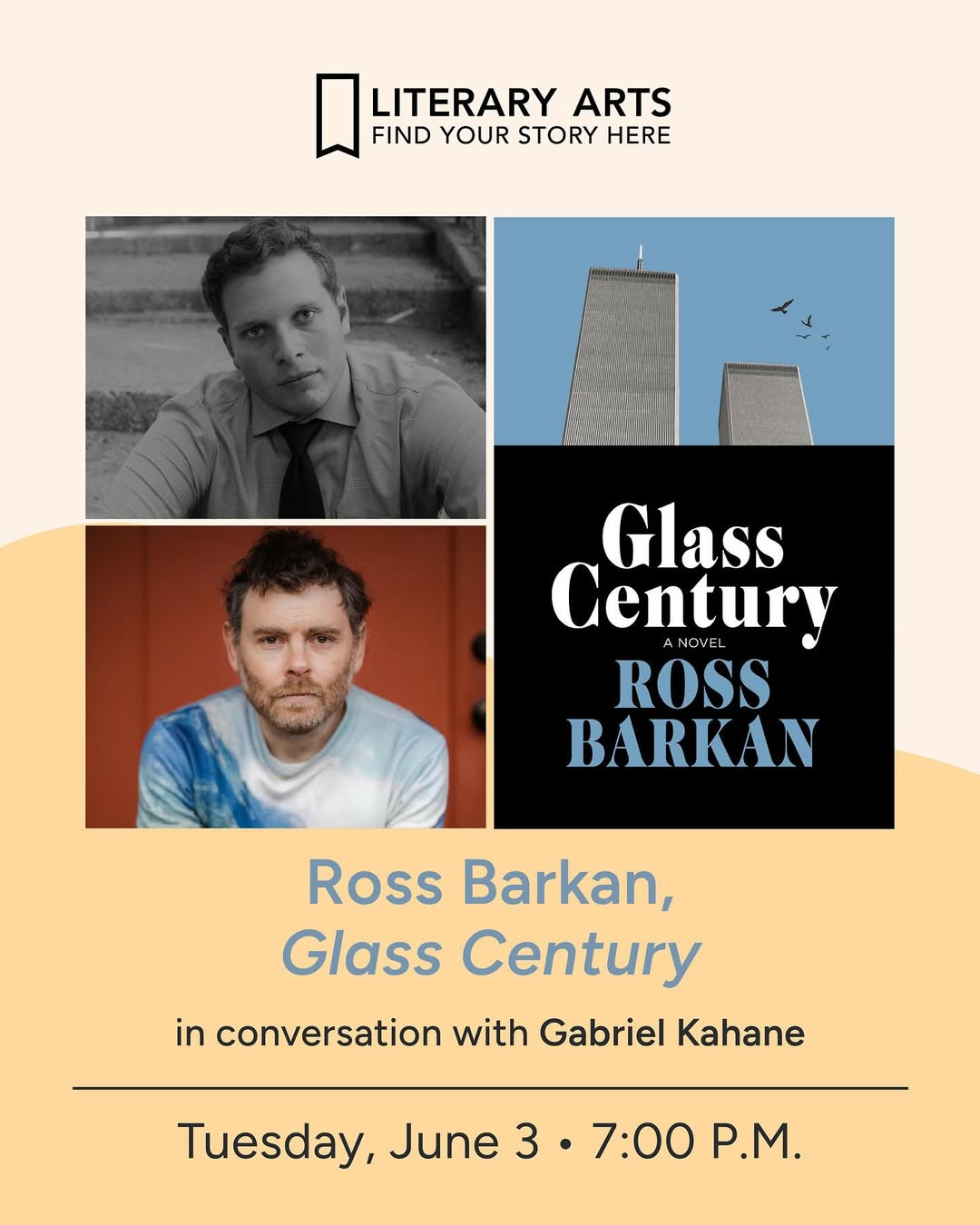

On the horizon: on Tuesday, June 3rd, I’ll be in conversation with

at the Literary Arts Bookstore, talking about his splendid new novel, Glass Century. The event is free and open to the public. I might sing a few songs. On June 20th, I’ll sing “October 1st 1939/Port of Hamburg” and conduct the Sarasota Festival Orchestra in a performance of my piano concerto, Heirloom, with my father, Jeffrey, as soloist. And on June 26th, I’m doing a solo house concert in Portland. Email here for details. As always, thank you for reading, and to those of you with paying subscriptions, for the financial support that makes this newsletter possible.While I was never seduced into making “streambait,” I can attest, anecdotally, to the accuracy of this last observation. My most-streamed track on Spotify is a song called “Little Love,” one of the simplest and “chillest” tunes I’ve ever released. As of this writing, it has been streamed 3,384,976 times. By contrast, the ten songs on most recent album, Magnificent Bird, have, cumulatively, been streamed fewer than 250,000 times.

“Averaging” is the operative word here; as previously noted, Spotify pays royalties not per stream, but on a pro rata basis, which means that major labels and viral hits command a larger percentage of total revenue than they would under a per stream or user-centric basis. For more detail, check out this essay.

To put these numbers in context: if I self-release an album, it costs roughly $7 to produce a vinyl record, which I might then turn around and sell for $20. At the “full” royalty rate of $0.0035, I’d need 3,714 streams to equal the $13 profit of a single LP sale, or 371 complete spins of a ten song album. If I were to opt into “Discovery Mode,” I’d need 5,416 streams to make that same $13, or 541 spins of the entire album. Now, if I were releasing with a label, those royalties would shrink by anywhere from 50 to 80 percent, depending on the deal. The numbers only get uglier.

Dear Gabriel!

Thank you for this (once again) thorough and thought-provoking essay. This time, however, I’d like to add something. You touch on this issue briefly, but I feel that the problem began elsewhere, and that Spotify is not the creator but rather the exploiter of a phenomenon — one that, in true capitalist fashion, it has managed to refine into a perfected form of exploitation.

Back when I was still teaching at the University of Theatre and Film Arts in Budapest (which, like so many other institutions, has since been ruined by Orbán), I would begin my classes by asking each student to introduce themselves through a piece of music that had meant something to them recently. What I often witnessed was that, while listening together in class, students would suddenly notice details they’d missed before — or, in more awkward cases, realize that the track they had chosen was, when listened to properly, actually quite boring.

I have the sense that a significant part of society has forgotten how to truly listen to music. We live in constant sonic clutter; most environments are shaped by an unspoken pressure that something must always be playing in the background. Music has been degraded to mere noise — or at best, ambient decoration — its importance reduced to that of a throw pillow or a scented candle. Even among musician friends, background music often plays during conversations, which I find more distracting than atmospheric. How am I supposed to discuss the crisis of European politics or share thoughts about a recent powerful film experience while a world-changing saxophone solo blares behind us?

Why are we so afraid of silence? Why does it now feel unusual when a restaurant doesn’t have music playing? Why have so many forgotten that listening to an album from start to finish can be just as cathartic as reading a novel, watching a film, visiting a museum, or going on a hike?

The key difference is that people tend to devote their full attention to those other experiences.

We as musicians share some responsibility in this. We can speak up when music is too loud or disruptive. We can also say how refreshing it is when a space doesn’t feel the need for constant background sound. And perhaps even more importantly: we ourselves should keep having powerful album experiences. We should seek them out, listen deeply, so that when someone asks us about the last record that truly moved us, we can recommend something that shook us to the core — something we couldn’t stop listening to and that still haunts us. Because there are so many of these miracles. Every day, our fellow musicians are recording bold, intimate, emotional, exploratory music.

When we share these with each other, we build community. We give others the chance to experience the same kind of wonder we did. And we give creators the chance to reach people with something into which they poured their lives, their faith, and who knows what else — something that, if it’s up to Spotify, will vanish into the digital void, never to be heard at all.

Required reading.