Having nothing whatsoever to do with the ongoing incineration of democracy in the good ol’ US of A, I’ve been finding it difficult to complete pieces for this here newsletter. Perhaps like some of you, I’ve been caught between, on the one hand, an awareness that repressive regimes thrive on public passivity, and that we should therefore do all we can to avoid paralysis, and, on the other, a strong urge not to allow the ongoing assault on institutions and civil liberties to be normalized by slipping into business-as-usual mode. What seems clear is that neither the Democrats nor the courts will save us. If we are to turn back the tide of authoritarianism, we’ll need a mass movement rooted in people power, which will require a degree of solidarity and collective action we’ve not seen in the United States in the last half-century.

Faced with this daunting task, many of my friends seem to be slipping into despair. Several have noted what they perceive to be my relative optimism amidst the 24/7 parade of terrible and terrifying news: here is our federal government, shredding the constitution, civil liberties, and, yes, shredding itself, with equal measures of glee and impunity. It’s horrific. A nightmare. Reader, I am not optimistic. But neither am I resigned.

To be clear, if one’s vision of civil resistance is limited to the post-millennium United States, a sense of hopelessness isn’t surprising. Recent protest movements in the U.S. have often failed because a) they mistook marches and rallies for strategic civil resistance, b) their demands were hazy and/or coopted and neutralized by elites, and/or c) their rapid growth—aided by social media and the internet more broadly—concealed structural weaknesses: lack of solidarity and trust, inexperience with organizing, and lack of disciplined messaging that could appeal to the broadest possible coalition.

I want to dwell for a moment on this last point involving the double-edged sword that is digital communication. Most people know that we cannot post our way out of authoritarianism. But neither can we rely solely on social media to organize our resistance. There are at least two reasons to pursue mass mobilization beyond our feeds: first, where social media networks tend to be ideologically homogenous, successful movements against repressive state power draw strength from the widest possible cross-section of society. Why? Because defections from the regime occur most readily when those tasked with carrying out its orders see their friends, family, or colleagues protesting against it. Second, as I mentioned above, speed is as much a liability as it is a strength in the realm of civil resistance, offering a perilous shortcut around the painstaking but necessary work of person-to-person movement building.

Yes, you can get a million people into the street in a matter of weeks or months via the internet, but you cannot necessarily sustain a lasting movement through such means. Effective organizing can be painfully slow. To wit, civil rights icon A. Philip Randolph began dreaming in 1941 of what would become the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which was a catalyst for the legislative civil rights victories of the 1960s. For those of us who’ve come of age in an era of frictionless digital communication, it’s difficult to conceive of the sheer volume of logistical work that went into planning such actions: the mimeographed pamphlets, the carpools, the meetings, the consensus building, and so on. This drudgery had an upside, for the movement grew more resilient and mature precisely as a result of all of the mundane tasks required of it, which, in bringing people together physically, offered countless opportunities to build solidarity across difference. Indeed, as the sociologist Zeynep Tufekci has argued, the 1963 March on Washington represented not just hundreds of thousands of bodies, but fearsome organizational capacity.

That organizational capacity is as crucial now as it was then. While marches and rallies have value, actions that target a state’s economy—strikes, boycotts, work stoppages, walkouts, etc.—tend to be the ones that topple repressive regimes. And these tactics can be sustained only with robust preparation: the stockpiling of resources, food, currency; the creation of mutual aid networks and alternate institutions. In sum, these tactics demand organizational heft.

Herein lies a paradox. How is a movement supposed to organize strategically and methodically, to build trust and resources—all of which take time—when we’re in the midst of what has been described as a five-alarm fire? Or, to take the opposite view, how do we make better use of digital technology, given that nonviolent movements of the last decade—many of which relied heavily on mass gatherings and social media—have failed at a higher rate than those between 1905 and 2010?1

With respect to the question of urgency, I trust that there are experienced organizers and activists puzzling over this question as we speak. They might agree that the repressive conditions faced by past nonviolent resistance movements were objectively harsher than what we are currently dealing with. This isn’t an invitation to slow down, but merely to point out that prior to the advent of texting, email, and social media, movements had no choice but to gather force gradually over time. This may be cold comfort, but it’s worth bearing in mind.

On the digital communication front, perhaps because of my past attempts to understand it, I have somewhat more concrete ideas. Social media sorts us culturally and ideologically. It likewise trains us to seek attention through performative pugilism. Indeed, our feeds, which privilege polemic over dialectic, have made it more difficult for us to countenance disagreement in just about every realm of life. And yet building a revolutionary movement to restore democracy—while rooting out the yawning inequality that has led to its collapse—will require a coalition beyond leftists and liberals. As the noted organizer Bernice Johnson Reagon said, “If you're in a coalition and you're comfortable, you know it's not a broad enough coalition.”

Building such a coalition will require us to unlearn bad habits we’ve developed as a result of our digital routines: the dunking, the name-calling, the contempt. I feel a bit like a broken record, but again, demonizing or dehumanizing our political opponents is a losing proposition, even when they dehumanize us. (Dr. King: “Nonviolence is directed against evil systems, forces, oppressive policies, unjust acts, but not against persons.”) As former Trump supporters increasingly lament that they “did not vote for this,” the knee-jerk, vindictive responses ranging from FAFO memes to “yes, you did vote for this” will be neither morally nor strategically sufficient. We should be grateful for allies, even and especially when they emerge from unexpected cultural or ideological spaces. What we must not do is dismiss or ostracize anyone who is also outraged by the hard authoritarian turn we are witnessing.

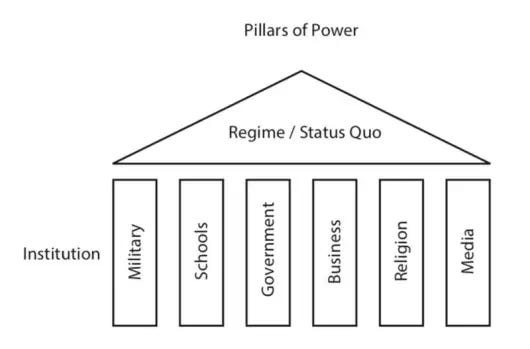

As terrifying and destabilizing as that turn has been, it’s important to bear in mind the counterintuitive frailty of authoritarianism. As political scientist Erica Chenowith argues in Civil Resistance, repressive regimes are more fragile than they appear, and are seldom monolithic. “Every oppressive system,” writes Chenowith, “leans on the cooperation and acquiescence of the people involved in what activist and intellectual George Lakey calls its ‘pillars of support.’” These pillars are different in every society, but generally include security forces, economic elites, bureaucrats, media, religious institutions, and schools.

Examining the Trump Administration through this lens, we may observe that behind the mask of power lies a loose and precarious affiliation of competing interests. Indeed, after just two months, hairline fissures have appeared, suggesting that the regime’s consolidation of power is provisional. Take, for example, the military. In the wake of Signalgate, U.S. servicemen were reportedly furious with the reckless behavior of Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, whose “we’re bombing Yemen” texts would have gotten him fired in any normal administration. Meanwhile, business elites have begun to express skittishness with the administration’s tariff scheme, while media, including traditionally conservative outlets like the Wall Street Journal, have maintained their independence in spite of a sustained campaign of intimidation. Yes, some institutions have capitulated, and this is cause for real concern. But dissent is in the air.

And beyond these institutional pillars, the lay public has not been shy about expressing its frustration with an unprecedentedly corrupt administration that seeks to dismantle the administrative state while pursuing more tax cuts for the rich. Countless Americans, Republican and Democrat alike, have laid into their elected representatives, leading GOP leadership to recommend a cessation of town halls for fear of more unflattering viral moments like this one.

So what is to be done in order to translate growing disenchantment with Trump’s authoritarian turn into meaningful opposition?

I want to offer a few suggestions, which are as much for me as they are for you:

Remember, with Dr. King, that our enemies are evil systems, and not people. Cultivate grace and generosity in every human interaction.

Take action, but prepare for, and embrace, a long campaign of resistance. Our era of instant gratification makes it difficult for us to accept that substantive change takes time. This is a particularly maddening reality to accept when we are faced with images of legal residents being snatched from the street while cabinet members conduct ghoulish photo ops in front of caged prisoners.

Educate yourself, and others, in the history of nonviolent movements. There’s inspiration to be drawn from the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, Polish Solidarity, the daring and inventive use of la cueca by Chilean women to protest Pinochet, the Singing Revolution in the Baltics, or any number of other successful campaigns that brought about regime change or extracted major concessions from those in power. I found Erica Chenowith’s book, Civil Resistance, to be an excellent primer. (It’s currently on backorder, which is a good sign!)

Use pillar analysis to assess vulnerabilities in support for the regime, and work collaboratively with others to undermine them further. At the same time, participate in the development of mutual aid funds and networks, which will be crucial when lengthy, large-scale strikes and boycotts are activated.

Work with intention to develop relationships outside your normal social spheres. Instead of sparring with people in public digital spaces, consider moving these conversations to a private sphere—even your DMs will do!—in which you can seek understanding and even consensus.

Find something to do in your own community. Authoritarianism succeeds when communities are divided. Strengthening yours will make those attempts at division more difficult.

And yes, joy! Find joy! It’s a real thing! We need laughter, tears, beauty, and irreverence to get us through the muck.

I began by writing about the tension between action and paralysis in the face of authoritarianism. It is all too easy to feel that one is not doing enough. But be kind to yourself. We cannot be all things to all people. Some of us will run for office. Some will give legal aid to immigrants facing deportation. Others will organize boycotts, marches, or conceive improbable acts of creative resistance. Still others will work to strengthen their communities in subtle but substantive ways, ensuring that when the regime attempts to turn people against each other, these efforts will fail. And yes, those of us in the arts have a role to play, unleashing beauty to do its inarticulable but essential work on the heart, mind, and body.

Speaking of which: this Friday (4/4), under the auspices of the Oregon Symphony and its Open Music series, I’m doing an unusual solo concert in Portland, Oregon, where I’ll be singing songs by a slate of some of my favorite songwriters, including Connie Converse, Charles Ives, Haley Heynderickx, SZA, Joni Mitchell, Randy Newman, and more. In the second half of the concert, I’ll introduce a set of brand new tunes of my own, written over the last couple of months, and in need of some tire-kicking. I’d be delighted to see you there.

If you are a regular reader of this newsletter, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription, which will allow me to dedicate more time to write, think, and dream. And to those who’ve already done so, I’m incredibly grateful for your support!

I’m drawing here from research collected in Erica Chenowith’s book Civil Resistance, mentioned elsewhere in this post.

With an election looming in Australia, we have two dominant parties running at about 50/50. One is drawing on Trump tactics and policy; the other is equally subservient to the fossil fuel and gambling lobbies, but is jogging rather than sprinting in their service. So whatever the outcome, this post is sure to be something I keep coming back to in the years ahead. It reminds us to fight the power that undermines our democracies, rather than the people giving in to (and probably deceived by) that power. Thank-you, as ever, Gabriel, for your thoughtful and compassionate writings.

Insightful and eloquent. Thank you for sharing this!