On finding grace in a cruel world

An essay about the impetus behind my solo shows; NYC premiere of 'emergency shelter intake form,' Playwrights Horizons engagement extends, and more...

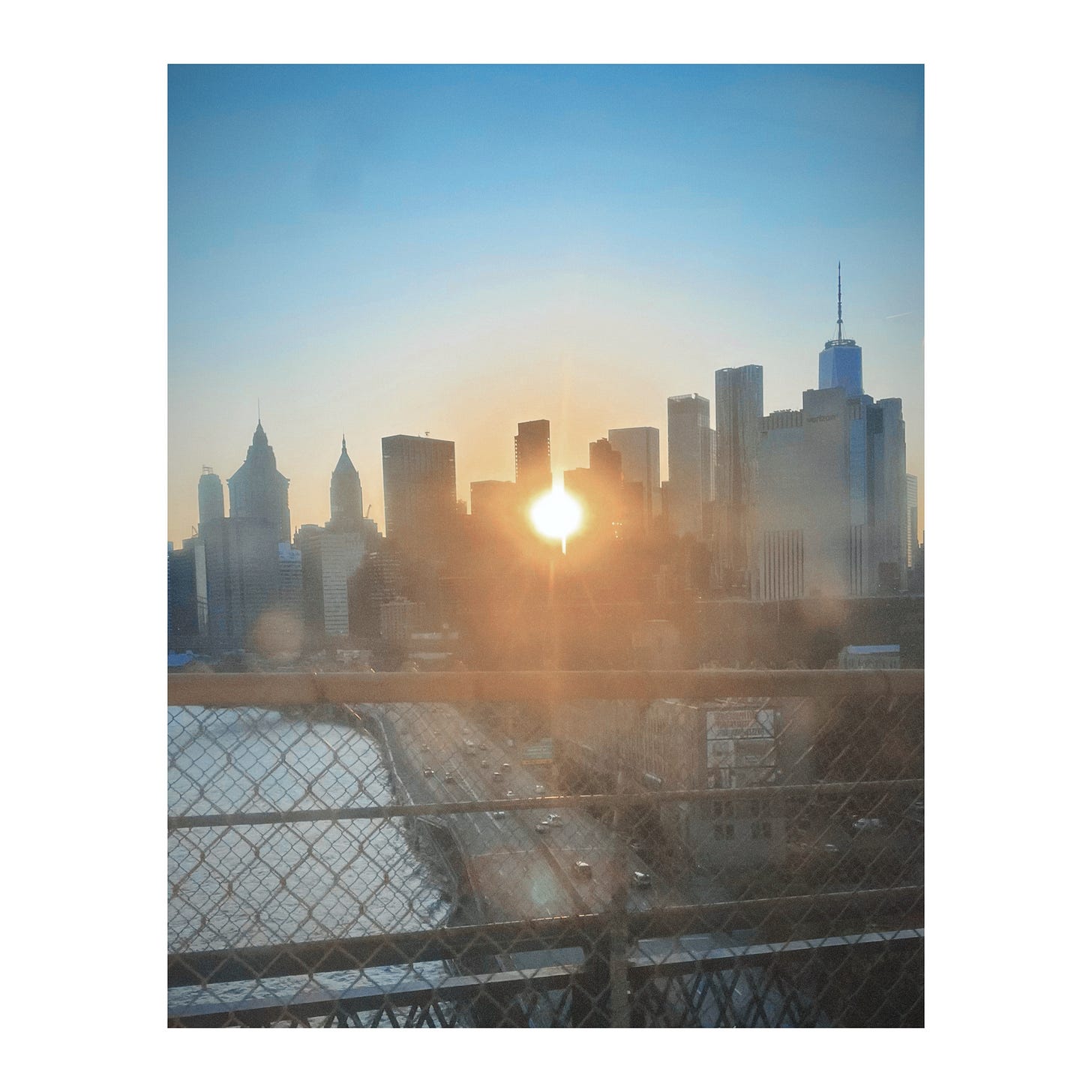

Greetings from New York, where I’m in rehearsal for my twin solo shows, Magnificent Bird / Book of Travelers, which I’ll perform in repertory at Playwrights Horizons beginning September 24th. Tickets for the engagement, which has been extended to October 13th, can be found here. The team at Playwrights asked if I would write something about the shows, and encouraged me to share it here as well.1

On finding grace in a cruel world

I.

I was sitting at my kitchen table in October of 2016, reading another breathless essay that sought to explain the shifting dynamics of the electorate, when I decided to get out and see the country for myself. I was tired of being a passive observer, of relying on pundits to catalog and contextualize the fresh wounds and faint scars that covered the body politic. I wanted instead to develop my own understanding—however provisional and incomplete—of what had led to this unprecedented moment in American political life. I told my partner that I was going to board a train the morning after the election and travel the country. I booked a loping, circuitous route: New York to Chicago to Portland to Los Angeles back to Chicago to New Orleans, and finally home to New York. In undertaking this journey, I would travel 8,980 miles over thirteen days.

The experience—which would yield the songs that became the album Book of Travelers—was by turns bracing, joyous, mournful, unsettling, monotonous, hair-raising, and transformative. Contrary to what we’re told on social media or cable news, people are complicated! They are full of contradictions! You don’t know what someone believes or why they behave the way they do unless you actually talk to them. I’ve often thought of my train trip as an attempt to transcend cultural and partisan division. But now, on the eve of the tandem presentation of these two music-theater pieces—each preoccupied in its way with the vexed relationship between human society and technology—it strikes me that the sheer lack of mediation on the train might have been as significant as the substance of the conversations I had with one hundred or so of my fellow passengers. I remember sitting in the observation car of the Southwest Chief, somewhere in the New Mexico desert, thinking to myself: some part of you is being healed and humbled by this experience, and you ought to cultivate more opportunities to exist, in this way, in the world.

Almost exactly three years later, I began a year-long hiatus from the internet, with the intention of doubling down on that commitment to engage with people, rather than devices, whenever possible. For a variety of reasons—the pandemic among them—the experiment didn’t go according to plan, and I spent the final eight months isolated with my wife and young daughter in an unfamiliar city. As much of the world became ever more reliant on the internet, I turned monkish. I considered abandoning the project, but persevered, whether out of foolishness or stubborn temperament.

While my digital detox grew from a desire to better understand the attention economy, surveillance capitalism, and the debts that accrue in our obsession with convenience and efficiency, Magnificent Bird—written mostly at the tail-end of my year offline—is not “about the internet.” In its formal and thematic restlessness, I’m not sure I could tell you what it is about. Formally speaking, it’s a weird hybrid that exists at the blurred edges of concert, confession, stand-up comedy, literary lecture, gonzo journalism, and theater. When I hunt for thematic unity, I perceive an undercurrent of loss running through the songs. Ours is a moment in which global communication has made us aware of more human suffering than one person can meaningfully hold. Many of us live in a constant state of emotional triage. Perhaps this is another reason we resort to tribalism: it simply hurts too much to be present and accountable to all of the pain that surrounds us. I suppose that, in writing these songs, I was asking myself this question: how can a person find grace, meaning, and purpose, in a world suffused with relentless cruelty?

II.

In societies that operate within a gift economy, writes the poet Lewis Hyde, the circulation of a gift—as it is passed from person to person—articulates a community. If you receive the gift, it is an indication that you belong. I believe that all performance is a gift, and that the artist and audience collectively make up a community. When I sing a song, it’s nice if it’s beautiful, but perhaps its holier function is to serve as a social bond. Sound moves through a room, and, if we are alive to the moment, we all become connected.

Not only in the aftermath of pandemic lockdowns, but in an era of extreme social isolation, one in which, for all of the marvels of digital connectivity, Americans are lonelier, more atomized, and more politically and culturally divided than ever, I’ve come to see my job as a performer as a kind of secular ministry. Here, I am less an artist on a pedestal than a shepherd of, and participant in, communal experience. On the train, I sought to expand my conception of the word “we”: to work through discomfort and against assumptions and biases in order to see myself in those who are very different from me, and vice versa. There’s something related at work in the plays I’m performing, in which songs, stories, confessions, and jokes, are instruments meant to awaken and expand a community, if only temporarily, within the walls of the theater.

Having lived in New York from 2003 til early 2020, it’s personally significant to be returning to the city to tell two stories, which are, in no small part, about leaving the city. But it’s also a layover on a longer artistic journey. I’ve been touring as a songwriter for fifteen years, and it’s only with these shows that I think I’ve found a form that’s specific to who I am: a vessel for my interests in music, storytelling, literature, journalism, cultural criticism, and history—but most of all, an arena in which to express and nurture my love of humanity, and my desire to see a society flourish in which we are unequivocal in the care we extend to all of our neighbors, in unyielding pursuit of the beloved community.

P.S. I’m pleased to share that the New York premiere of my housing oratorio emergency shelter intake form will take place on October 24th at Trinity Church, with the NOVUS new music orchestra under the baton of Daniela Candillari, with soloists Alicia Hall Moran, Holland Andrews, Holcombe Waller, and me. The day before, Trinity Choir will give the NYC premiere of two choral works I’ve written. Admission is free; reservations will be available in the coming weeks.

I lifted a sentence or two for the essay from previous pieces here; apologies for the auto-shoplifting.