On Songwriting: Part I

Stories, characters, the unconscious mind, and the perils of rhyme

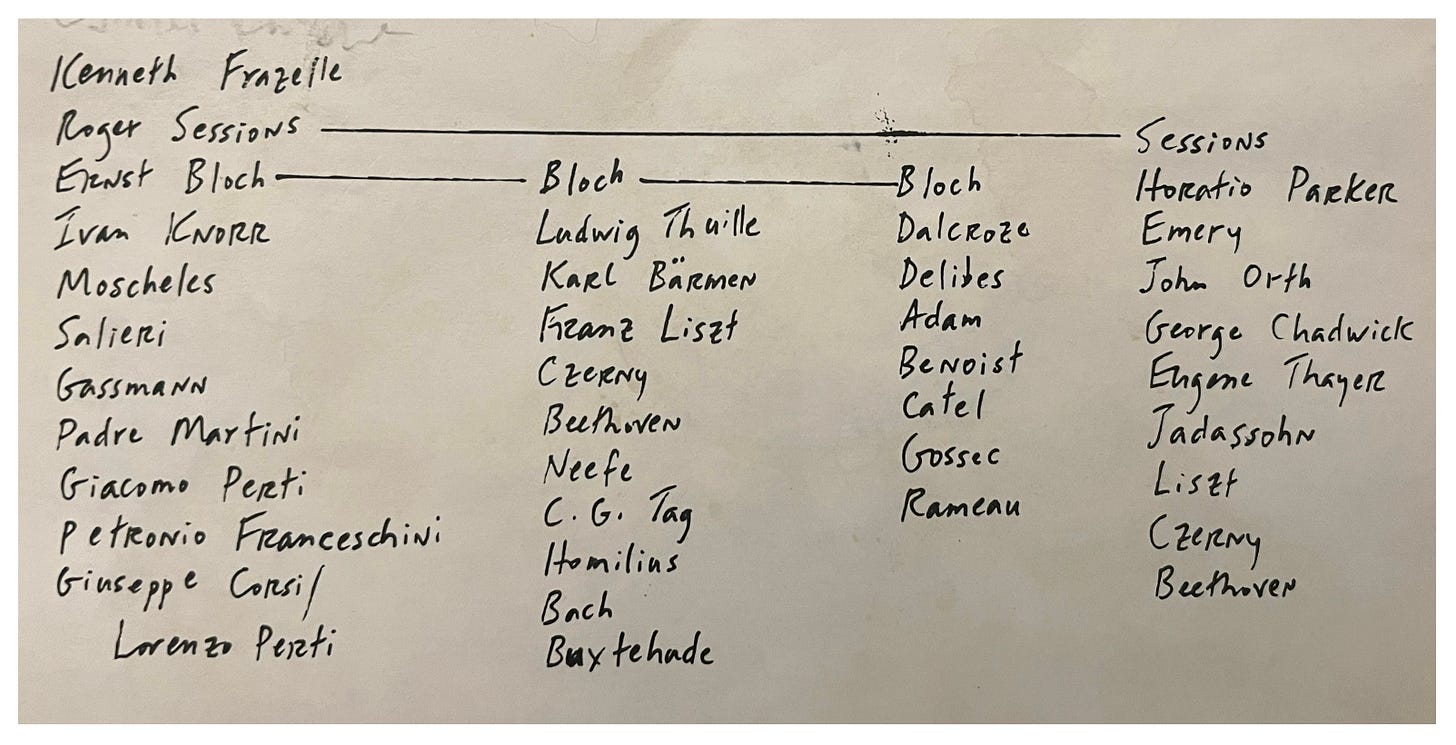

For the last decade, I’ve had an open door policy when it comes to teaching. If someone reaches out over the transom asking for a lesson, I nearly always consent. I’ve long believed that a well-rounded musician has an obligation to participate, however sporadically, in the transfer of knowledge from one generation to the next. When, in my early twenties, I began to study with Ken Frazelle—the only composition teacher I’ve ever had, and someone whose wisdom continues to inform my creative decision-making twenty years later—he handed me a photocopy of a handwritten family tree, which showed that, pedagogically speaking, I was now eight generations removed from Beethoven, and only four more from J.S. Bach.

But last week, surveying the mountain of work I’ve committed to and the shortage of hours in which to complete it, I realized that something had to give. No more teaching, I decided, at least until 2025. (I don’t have any regular students, so I wasn’t reneging on long-term commitments, just the odd one-off here and there.)

As I wrote apologetic notes to a few folks who’d asked for an hour of my time, and offered instead to answer questions via email, it occurred to me that I’ve never attempted to organize in writing my thoughts about the craft of songwriting. And since this is, after all, a blog called “Words & Music,” it seemed appropriate for me to hold forth on the subject. (Drum roll, swelling brass, piercing triangle tremolo.) Lo, here is part one in a series of essays on songwriting.

(Note: a playlist with all of the songs mentioned can be found here.)

Preamble: Chicken or Egg?

As a songwriter, I envy those who have a routinized approach to their craft. Several tunesmiths I admire write music first and then reverse engineer a lyric to fit the melody. This may seem counterintuitive, but it worked for Bernstein and Sondheim, among other legendary American musical theater teams, not to mention several singer-songwriters who are among the best lyricists I know.1

Others, many folk singers among them, sketch a lyric first and then find the melody and chords. One merit of this approach is that it allows the words to dictate musical choices that might not emerge otherwise: unusual phrase lengths, say, or complex time signatures.

As for me, I don’t have a fixed system. But for each of the roughly four methods I use—1) story/character first, 2) lyrics first, 3) music first, 4) song-as-étude—I have some semblance of a ritual.

I. Story/Character First

Sometimes I encounter a story that wants urgently to be translated into song. When I was working on my third album, conceived as a love letter to Los Angeles, I knew there would be a tune about the Ambassador Hotel, fabled for its rich Golden Age Hollywood history and immortalized by Bobby Kennedy’s assassination in June of 1968. The challenge was to come up with a point of view and a temporal frame.

In film criticism, biopics are often criticized for collapsing under the weight of completism, where the impulse to be comprehensive results in lack of focus. The same goes for any narrative art form: indeed, more often than not, craft lies not in being exhaustively thorough, but in identifying a single event that serves as a dramatic fulcrum.

When I stumbled upon an article about The Ambassador’s longtime night doorman, Arthur Nyhagen, I knew I had a way in: I would write from his point of view, on the eve of the hotel’s closure in 1989; his personal history would serve as a conduit to the hotel’s past. With all of that in mind, I began, as I often do, with freewriting.

Art-making requires a balancing act between the conscious and unconscious mind. As a general rule, the unconscious mind is most useful (to me) in the early, generative stages of the creative process, whereas the conscious mind becomes indispensable when I turn, later, to editing, organizing, clarifying. If I proceed hastily toward rigorously structured lyrics, I often end up shackled to formal concerns: rhyme, meter, line length.

Rhyme is a device that helps the listener to better absorb a lyric. There can be surface or intellectual pleasure in rhyme, but it seldom, in and of itself, transmits emotion. To be prematurely fixated on rhyme is to make image, story, character, and psychology—everything that gives a song its staying power—subservient to artifice. Freewriting, on the other hand, unleashes the unconscious mind, encouraging an unfiltered and intuitive approach to all of the above. Moreover, freewriting makes for a more playful relationship to language: adjectives find new nouns, nouns make new verbs, and so on. In my process, rhyme may come late in the process, like finishing salt on a slice of crusty bread drizzled with olive oil.2

Oftentimes, story and character are inextricably linked. “What If I Told You,” from Book of Travelers, is a distillation of a two-hour conversation I had with a woman on a train from Chicago to New Orleans just after the 2016 election. When I set out to write the song six months later, I knew precisely which part of the conversation I wanted to relay, and used the journal I’d kept on the train as a loose first draft. But what if there’s someone you find fascinating (real or fictional), you want to write a song about them, but aren’t sure where to start? (“Baltimore” and “Friends of Friends of Bill” are examples of tunes that grew out of this kind of impulse.)

In such cases, there’s a forking path: either 1) I search for an action or story through which a character study emerges, or 2) I use a character’s psychological interiority—the movement of the mind—to sustain the listener’s interest and create emotional ballast.3 Either way, I find freewriting to be an essential resource in getting started.

II. Lyrics Come First

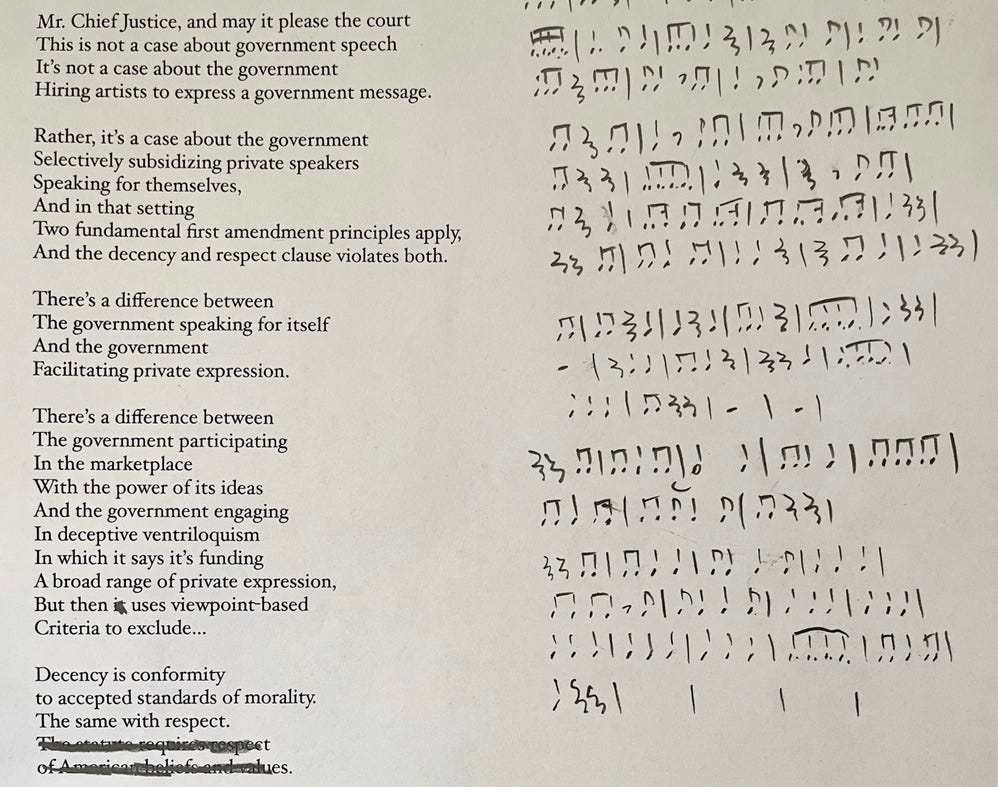

For all the reasons I described above, lyrics tend to emerge, for me, out of freewriting. Across several drafts, I begin to find a shape, massaging images and events into a coherent structure.4 Once I have a draft, I’ll proceed in one of two ways. The more deliberate approach—which I also use when setting words I didn’t write—involves printing the text, and then, in pencil, sketching rhythms on the righthand side of the page.

I began using this technique almost twenty years ago, after reading that Johannes Brahms, when writing songs, did something similar. He would very lightly print the text of a poem onto a sheet of manuscript paper, and in faint pencil, add rhythms (but no notes). This technique is particularly useful in helping to reveal the internal logic of a text that lacks an obvious rhyme scheme. By focusing on rhythm, I can quickly map out different structural possibilities before getting overly invested in other musical elements.

On the other hand, if a lyric is written in fairly straightforward meter—say, quatrains with lines of eight syllables and an ABCB rhyme scheme—or if I’ve only got a fragment, I’ll often move to the piano or guitar and begin to improvise. Once a basic musical structure is in place, I might then begin to revise lyrics. And, boy, I am a chronic reviser. I’ll often write a hundred lines in order to get twelve not-terrible ones.

Sometimes, when the sentiment of a line or stanza causes it to deviate from the structure I’ve set up—a few extra syllables; five lines instead of four—I’ll adjust the music rather than force the lyric to conform. Often, these oddities give a song its character. (In “We Are the Saints,” for example, an irregular set of lyrics determined the digressive harmonic sequence in the second verse.) For me, one of songwriting’s greatest pleasures is the tension between traditional structure and formal invention, and the search for new ways to throw my weight against the limits of song form while arriving at something coherent.

As we wrap up the first part in this series, I want to say something more about economy of language. Songs, like short stories, demand ruthless efficiency, through which a single detail can conjure a world. If you’ve limited yourself to three verses, a chorus, and a bridge, then you’ve got to be merciless in making every word count. When I work with young songwriters, I often encounter tunes in which an entire verse is spent expressing an idea that could be conveyed in a single line. This has the effect of allowing the listener to get ahead of the story, and thus to lose interest in it.

But it’s a balancing act. Just as often, the lyricist who fears being overly direct will obscure the action of a song to such an extent that the listener is left entirely in the dark. If your tune requires a preamble along the lines of “this next song is about…”, then you may want to take another look at your lyric with an eye toward language that will better illuminate the scene. And that, of course, is the whole game: achieving clarity while leaving negative space for the listener to make meaning.

One strategy I find useful, once I’ve found the form of a lyric, is to outline the action of each verse. How much can be corralled into a single stanza? Or if we think of the lyric as a film, then where, line by line, is the camera? Is the verse a series of rapid, seemingly disjointed images, which finds its logic only in the wide-shot chorus, revealing a city seen from above? Do we start wide and gradually zoom in, landing on the image of two lovers holding hands at the edge of the sea? Or perhaps the first two verses offer medium shots of a subject, setting up an expectation that is broken in the third verse, at which point we careen into a rapid-fire montage that collapses 75 years into a few lines.

I can’t stress enough the importance of being patient with lyrics. You never know when a few words will reveal the logic of an entire song. But sometimes it’s only on the thirteenth draft that those words materialize. Of course there are songs that arrive more or less fully formed, and if it’s working, let it be. Don’t tinker for tinkering’s sake. The battery of resources I’m laying out here are for those days—most of them, in my case—when writing is a painstaking game of inches.

(To be continued…)

I’m not naming them, as I don’t think it’s my place to discuss the creative habits of others.

Hat tip to my best bud Tamar Adler, whose newsletter, The Kitchen Shrink, is indispensable.

Theater music—and how character is approached in that context—is another kettle of fish to be seasoned and sauced another day.

The act of migrating from inchoate stream-of-consciousness to finished lyric is something I described in some detail a few years ago in a post called “Kill Your Darlings.”

Thanks for doing this!

> achieving clarity while leaving negative space for the listener to make meaning.

Yes! This articulated the goal I've been working towards myself. Balancing ambiguity and clarity. Really enjoyed this and looking forward to more.

Especially thinking of the medium's relationship to short stories. One of the most useful classes I've taken in songwriting was in George Saunders' book analyzing Russian short stories (A Swim In The Pond In The Rain). Similar to what you said in that every single word counts!